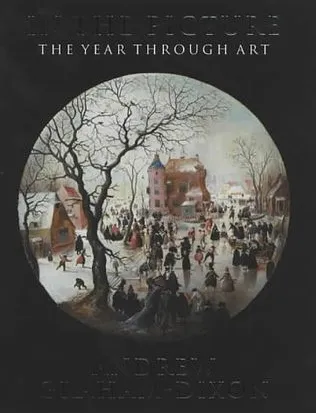

In the Picture: The Year Through Art

This is Andrew Graham-Dixon's account of an Indian work of art, Krishna with the Cowgirls, from his book In the Picture:

On the eve of the Indian spring festival of Vasanta Panchami, today’s picture is taken from the British Museum’s so-called “Manley Ragamala”, an album of paintings created in about 1610 by an anonymous artist working in an atelier attached to one of the courts of Rajput in Rajasthan. The literal meaning of Ragamala is “garland of melodies”, the term having been applied to albums of this kind because each of the many intricate and brightly coloured images that they contain was intended to relate to a specific sort of music, as well as to a distinct emotion and a particular time of year. The image reproduced here is the Vasanta Ragini, or “Vasanta festival melody”. It is not difficult to imagine the kind of mood and music which this highly animated depiction of Krishna dancing with the cowgirls of his legend was intended to conjure up. It must have been something joyous, life-affirming and even fairly riotous, to judge by the various instruments shown, which include the cowgirls’ own accompanying drums, cymbals, strings and tambourines, as well as Krishna’s own flute.

The blue-skinned deity has brought a vase full of flowers to his devoted lovers. Crowned with peacock feathers and garlanded with blossoms, he wears a splendid robe of bright yellow, which is Krishna’s traditional colour as well as one with a particular festive significance during Vasant Panchami, when the fields are carpeted with yellow mustard flowers announcing the onset of spring. Richard Blurton, Assistant Keeper of Oriental Antiquities at the British Museum, who consented with great good nature to be my tutor in the art of the Indian subcontinent, tells me the special vividness of Krishna’s robe in this picture is probably due to the artist having painted it in pure turmeric.

The subject matter of the painting is also quite spicy, although liable to require some explanation for those unversed in the cults and deities of Hinduism.The Hindu God is known according to his three functions: as Brahma, creator of heaven and earth and of all living things; as Shiva, the destroyer, source of reproductive energy and inspirer of asceticism; and, between these two extremes, as Vishnu, God in his character of loving protector and preserver. Krishna, who is one of Vishnu’s ten incarnations, was given his first leading role in the tangled drama of the great Indian epic, The Mahabharata, which gradually evolved between the fourth century BC and the fourth century AD. He appears there as a kind of feudal magnate, a bold warrior-prince and shrewd counsellor who only sporadically exhibits the signs of his divinity. His metamorphosis into the figure depicted in the Ragamala image reproduced on this page can be traced to the tenth-century text the Bhagavata Purana, and subsequently to a huge body of passionately romantic mystical verse written in India over the following seven centuries and more. In this literature, another Krishna emerged: not Krishna the Prince but Krishna the Divine Lover; who lives among cattle herders, charming all creation with his music; and who inexhaustibly makes passionate and ingenious love to a multitude of adoring gopis, or cowgirls, in the idyllic bowers of Vrndavana, a magical pastoral world perhaps not a million miles away from the Christian Garden of Eden.

The amorous Krishna’s favourite among the cowgirls is named Radha. The Indian poets excelled themselves in long descriptions of the god’s love for his humble human companion. Here is the Bengali fifteenth-century poet Vidyapati’s nakedly impassioned account of Krishna’s awakening feelings for Radha as she grows from girl into woman (like most erotic poetry, I suspect it suffers a bit in translation):

“Each day the breasts of Radha swelled.

Her hips grew more shapely, her waist more slender.

Love’s secrets stole upon her eyes.

Startled her childhood sought escape.

Her plum-like breasts grew large,

Harder and crisper, aching for love.

Krishna soon saw her as she bathed,

Her filmy dress still clinging to her breasts,

Her tangled tresses falling on her heart,

A golden image swathed in yak’s-tail plumes…”

Such poetry conveys the intensely sexual nature of the gopis’ relationship with Krishna (and vice-versa); and also helps to explain the current of emotion that runs through the anonymous early seventeenth-century Rajput court artist’s depiction of Krishna with the Cowgirls. The gopis in the painting are aflutter with excitement. One of them squirts Krishna festively with coloured paint from a pump, the spatter from which delicately flecks much of the lower left side of the picture, almost as if applied by aerosol (when I first saw it, I wrongly assumed it was damage to the painting). Several of the others dextrously manage to play their instruments at the same time as reaching out their adoring, supplicating hands towards the object of their affections. Their large and liquid eyes are filled with yearning, while their doubtless crisp and plum-like breasts seem palpably to swell and heave, aching for love. All around then, nature itself seems in a state of arousal. The river foams, flowers bloom, vegetation everywhere burgeons. In the background, a preening peacocks performs his own courtship ritual.

Radha, Krishna’s best beloved, is in fact absent from the scene. The artist seems to have represented the moment when, at springtime, the charming but also highly promiscuous Krishna abandons her to pursue the rest of the cowgirls. This incident is described beautifully in the Gita Govinda, or Song of the Cow-Herd, a twelfth-century Sanskrit poem by Jayadeva:

“Sandal and garment of yellow and lotus garlands upon his body of blue,

In his dance the jewels of his ears in movement dangling over his smiling cheeks,

Krishna here disports himself with charming women given to love.

He embraces one woman, he kisses another, and fondles another beautiful one.

He looks at another one lovely with smiles, and starts in pursuit of another woman.

Krishna here disports himself with charming women given to love.”

It would be a mistake, however, to read such poetry - and therefore images like Krishna with the Cowgirls - as straightforward erotic romance. Rather like the ecstatic writings of Western saints and mystics such as St Francis of Assisi, St Teresa of Avila, or St Bridget of Sweden, which describe the body and love of Christ in similarly sexually charged terms, such manifestations of the cult of Krishna were not seen as lewd or lubricious. The keen and yearning love of the gopis for Krishna was understood to express the profound yearning of the human soul for union with God. Word and image (and music too for that matter) were used allusively, to heighten the emotional pitch of devotion.

Just why the image of Krishna the Lover, ringmaster of romantic dalliance, should have become so immensely popular, all over northern India, from the tenth century onwards, is not easily explained. But W.G. Archer, in his 1957 study The Loves of Krishna, advanced a plausible hypothesis. “From the tenth century onwards,” he wrote, “a tightening of domestic morals had set in, further intensified by the Muslim invasions of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Romance as an actual experience became became more difficult of attainment and this was exacerbated by standard views of marriage…With the seclusion of women and the laying of even greater stress on wifely chastity, romantic love was increasingly denied. Yet the need for romance remained and we can see in the prevalence of love poetry a substitute for wishes repressed in actual life.”

The learned Richard Blurton would say the same is true of love painting, too: “The Ragamala images are imbued with an intense emotion, which I think is so to speak the other face of the incredibly rigid, hierarchical, family-dominated, caste-dominated society in which they were produced. I think people found release through painting, and music, and religion, which enabled all their feelings to flood out.” Looking at images such as this they could be (vicariously at least) both Krishna and his sexy consorts, enjoying a life quite apart from this life, by the side of a sacred river, in a green and fertile world of guiltless bliss.

Hardcover: 212 pages

Publisher: Allen Lane (6 Nov 2003)

Language English

ISBN-10: 0713996757

ISBN-13: 978-0713996753

Product Dimensions: 22 x 18 x 2 cm