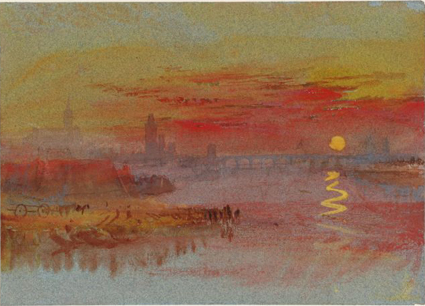

Watercolours at Tate Britain. By Andrew Graham-Dixon.

A year or so before the outbreak of the English Civil War, Anthony Van Dyck, Principal Painter to King Charles I, found himself somewhere by the coast in a quiet corner of rural England. He recorded the scene before him in the form of a modest watercolour painted on an oblong piece of paper roughly the size of a printer’s octavo sheet: a small copse, summer foliage dappled in sunshine, each tree casting its dark shadow on the ground; roofs and chimneys of a small village or port, just visible behind the trees; the masts of a flotilla of tall ships, silhouetted against the sky in the middle distance, each tip-tilted at a different angle by the heave and dance of the sea. The artist painted the moment, but he also painted the moment of its passing away: to the right of the sheet, he allowed the objects to drift into incompletion, ships’ masts turning into ghostly traceries of uncoloured line, land and sea melting into the whiteness of untouched paper.

Van Dyck’s A Coastal Landscape with Trees and Ships has been hung at the very start of "Watercolour", Tate Britain’s invigoratingly eclectic new exhibition. It is a surprisingly early example of the landscape watercolour and it has been chosen, presumably, because it demonstrates the principal strength of the medium –its ability to catch an experience while simultaneously suggesting the evanescence of all human experience, itself a ceaseless flow of images as shapeshifting as the movements, across paper, of pigment dilute in water. In the words of the sixteenth-century philosopher Montaigne, "There is no constant existence, neither of our own being, nor of objects. And we, and our judgement, and all mortal things incessantly change, turn, and pass away ...And if perhaps you...