“The Horse: From Arabia to Royal Ascot”, at the British Museum.

The British Museum’s Diamond Jubilee exhibition, “The horse: from Arabia to Royal Ascot”, is a breakneck gallop across continents and civilisations. Exhibit 1 (of around 250) is the so-called Standard of Ur – a triangulated block decorated with rows of figures in shell on lapis lazuli, approximately 4,600 years old, recovered by Sir Leonard Woolley during excavations at the Royal Cemetery of Ur in Mesopotamia. The original, practical purpose of this intriguing object is unknown (was it the sounding box of an ancient musical instrument?) but its ritual function is clear enough. It celebrates a victory in battle, stripped captives led away in chains by their conquerors. It also celebrates the newfangled technology that made that victory possible: manned chariots, drawn by comic-book steeds with quaintly bemused expressions on their horsey faces.

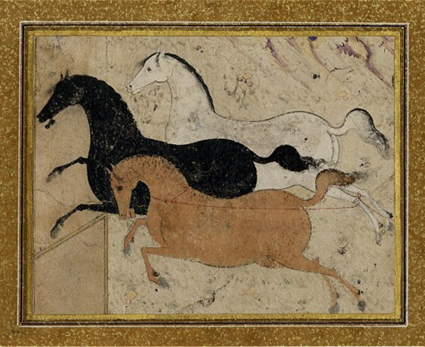

The creatures of Ur were probably asses or donkeys of some kind. They are certainly a far cry from the sinewy, muscled stallions pulling the chariot of two inscrutable, bearded, lion-hunting Assyrians, in a relief created all of 1,500 years later (c.875 BC) for the North-West Palace at Nimrud. They bear only a passing resemblance to the skittish, ancient Egyptian ponies who appear in a fragment of wall painting recovered from the tomb of Sobekhotep at Luxor. And they probably lack the resilient qualities of those battle-hardened chargers of the Middle Babylonian era whose praises are sung on a limestone stela erected by Nebuchadnezzar I to the honour of his charioteer-in-chief, Ritti-Marduk. But they are, nonetheless, among the earliest visible reminders of a great revolution in human history – a revolution brought about by the domestication of the modern horse and its ancestors. The horse transformed the practice of warfare and of hunting, and enabled men to...