When James Christie set up his auction business in 1766, his timing could hardly have been better. The British Empire was in its ascendancy. The aristocrats of Georgian England, their appetite for art stimulated by the Grand Tour – that obligatory journey of discovery to France and Italy, where as young men they would first stretch their aesthetic sinews and, with luck, pick up some Old Masters or antiquities along the way – were interested in painting and sculpture as never before. A good business got even better after 1789 and all that. The French Revolution gave further stimulus to the already thriving trade of “picture hawking”, as many of the great collections of the French nobility, surrendered perforce by their desperate owners, went under the hammer. Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, but to be a London auctioneer was very heaven.

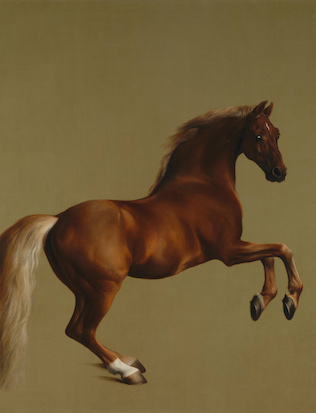

Christie was friends with a number of English painters, including Thomas Gainsborough and Sir Joshua Reynolds, founder of the Royal Academy of Arts. But he was rarely in a position to promote or sell their work. His aristocratic clients were simply not interested in British art. They had been brought up to believe that Great Art was, by definition, foreign art, preferably created by long-dead Italians or even longer dead Greeks. At home, the aristocracy might employ the painters of their native country, but grudgingly, and only to perform the relatively menial tasks of depicting “my wife, my horse, my house and myself.”

So it is a cheering measure of how much attitudes have changed that Christie’s should have chosen to celebrate this, its 250th anniversary year, with a grand sale of British art from the past three centuries, as well as a curated exhibition that gathers together a selection of British masterpieces...