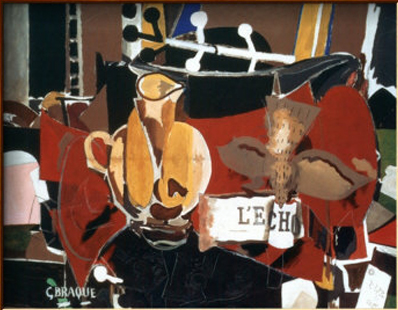

Georges Braque worked on his painting L'Echo for three years on and off before deciding, one day in 1956, that he had at last finished it. We see a tabletop covered by a red cloth on which stands a jug, beside which there is a newspaper folded in such a way that only a part of its masthead, "L'ECHO", is visible. Above this there hovers an inexplicable brown bird, wings spread like the dove of the Holy Ghost in Piero della Francesca's Baptism. The style in which Braque's picture is painted makes it impossible to tell whether the bird is clutching the newspaper in its beak or not. But ambiguities of that kind did not trouble the painter and he decided to leave it at that.

L'Echo has been taken to refer to the French newspaper L'Echo de Paris but, as Braque knew, his title was bound to be read metaphorically as well. The picture, like so many of Braque's later works, is itself an echo, recalling other pictures painted by the artist, long ago, when he was a much younger man. Objects on a tabletop, a scrap of printed text, painted trompe l'oeil, coexisting in a pictorial space furled in some places and flattened in others - how very Cubist, almost half a century after having invented Cubism, Braque remained. Not for him the constant self-reinvention of his fellow pioneer Picasso. "Braque: The Late Works", at the Royal Academy, is a study in persistence, tinged by sad retrospection. The pictures of the artist's last 20 years are, almost all of them, variations played on lifelong themes. Most are interiors, and many of those interiors turn out to be pictures of a painter's studio. This is a grave, often sombre art, almost painfully turned in on itself. The presiding...

Lonely echoes

28-01-1997