One of my favourite descriptions of any artist is Erwin Panofsky’s one-line summary of the fifteenth-century Flemish painter Hans Memlinc: “the very model of a major minor master”. Until reading it I would never have guessed that Panofsky, that nonpareil expert on early Netherlandish art and beetlebrowed iconologist, was also a fan of nineteenth-century musical comedy. For those unfamiliar with the work of Gilbert and Sullivan, the inspiration for Panofsky’s double-edged tribute to Memlinc was the the tongue-twisting signature song of their most famous comic opera, The Pirates of Penzance, namely “The Modern Major-General’s Song”:

“I’m very good at integral and differential calculus

I know the scientific names of beings animalculous

In short, in matters animal, vegetable and mineral…

I AM the very model of a MODERN Major-General.”

As regular readers of this column will know, I am always on the lookout for what might be called major minor figures in the history of art. Life is made more interesting by an awareness of their struggles and achievements, relatively untrumpeted though they may be (in addition to which first-rate examples of their work can still be acquired by the discerning collector whose budget may not run to millions). So who – with apologies to Erwin Panofsky and Gilbert and Sullivan in equal measure – might be the very model of a major minor MODERN master?

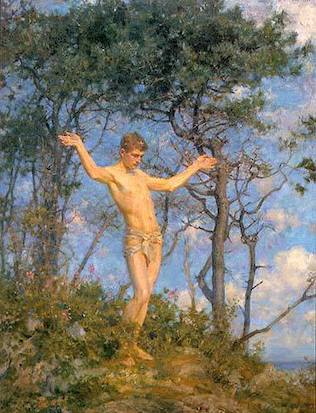

One candidate might well be an artist who was just embarking on his career when The Pirates of Penzance was first performed, back in 1879; and who, as it happens, was based for most of his working life in the Cornish port town of Falmouth, less than thirty miles from Penzance. I am thinking of the perennially underrated Henry Scott Tuke (1858-1929), who despite the constraints of late Victorian and Edwardian...