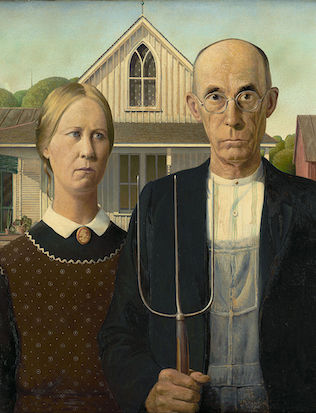

In 1930 an unknown American painter named Grant Wood decided to send one of his pictures to the juried annual open exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago. Much to his delight he won a prize, the Norman Wait Harris Bronze Medal, and with it $300 in cash: no mean sum for a struggling artist in his late twenties, born and raised on a remote farm in Iowa, trying to make his way in the provincial wilds of the American Midwest at the outset of the Great Depression.

Little did he know, but that bronze medal marked the beginning of one of the unlikeliest stories in the history of art. Wood’s prizewinning picture, portraying a hard-bitten farming couple and entitled American Gothic, was soon to be championed as the masterpiece of a new American art movement called “Regionalism”, first invented, and then promoted, by an impresario and art dealer from Kansas City named Maynard Walker. According to Walker, whose words carried influence, such work represented a robust all-American riposte to “the shiploads of rubbish that had been imported from the School of Paris” by the effete and gullible art collectors of New York. In American Gothic he saw a picture that dared to present real Americans, in all their true grit, to American eyes.

By the mid-1930s reproductions of Wood’s suddenly famous little picture were were to be found hanging in homes from Long Island to Los Angeles and everywhere in between. During the years that followed, it would be ceaselessly pastiched by the newspaper cartoonists of the day and just as often appropriated by the advertisers, in America’s first great age of advertising, who found it had the power to sell anything from electrical goods to bottles of bourbon. The only other twentieth-century painting to rival its...