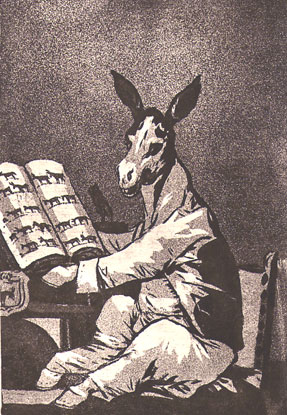

The mercurially brilliant Spanish painter, engraver and draughtsman Francesco de Goya y Lucientes (“Goya”, as he has been abbreviated by posterity) has been dead for more than one hundred and eighty years; but his influence continues to grow from beyond the grave, at an almost startling rate. His modern celebrity depends largely on the startling works of his later years: violently strange caprices, scenes of witchcraft, occultery and strange hauntings, populated by bats and a host of other creatures that fly in the night; deadpan, scarily benumbed depictions of war and its attendant horrors, rape, torture and famine; paintings of madness and disturbance, evil represented in all its polymorphous perversity. Most of these images were unsold and unexhibited in the artist’s own time, considered by his contemporaries – and perhaps by the artist himself – to be too troubling, too bizarre and too eccentric for public consumption. But it is precisely Goya’s weirdness and violence that seems to draw so many modern admirers to his work, like moths to a flame.

The most telling index of Goya’s accelerating popularity is the rising tide of books and commentaries inspired by his life and work. In the case of most long-dead painters a new biography might be expected to appear only about once in a generation. But in the case of Goya, no fewer than three have appeared (in English alone) in the last year. Hot on the heels of Julia Blackburn’s entertainingly self-deprecating biography-cum-travelogue, Old Man Goya – an accident-prone attempt at a journey to the heart of his darkness – come Werner Hofmann’s new study and a long-awaited biography by renowned Australian art critic Robert Hughes, the last weighing in at a substantial 400-plus pages. But Goya also haunts the contemporary imagination in other ways besides, cropping up...