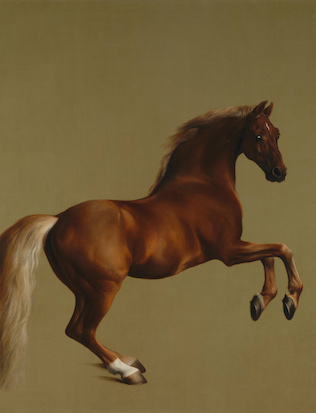

There are those who cling to the idea that they cannot be interested in the work of George Stubbs, England’s principal equestrian painter, because they are not interested in horses. But just as books should not be judged by their covers, artists should not be judged by their subject matter. The truth is that many painters have found unexpected depths of meaning in apparently mundane themes: think of Chardin's pyramid of strawberries, Cezanne's fractured apple, Picasso's Cubist absinthe bottle. Stubbs painted horses, that much is true. But he did far more than just that, just as he himself was far more than a mere animal painter, recording the appearance of those sleek thoroughbred horses ridden and raced by the milords of eighteenth-century England.

George Stubbs (1724-1806) was one of the greatest British painters to have lived, and the equal of any of his European contemporaries. A brilliant draughtsman, he possessed a control of line not seen in England since the time of Holbein. He was a deep thinker too, a painter-philosopher and scientist: a true man of the Enlightenment, whose work gave expression to great shifts in the texture of European thought. Small wonder, then, that the versifier Peter Pindar should have written “’Tis said that nought so much the temper rubs / Of that ingenious artist, Mister Stubbs, / As calling him a horse painter …”

Because Stubbs himself wrote little, his character and temperament remain mysterious. What can be said with certainty is that he was a slow developer and largely self-taught. Until he was about 16, he helped in his father’s leather-working business in Liverpool. He then found employment in the studio of a local artist of distinctly limited talents, one Hamlet Winstanley, who gave his new apprentice the edifying but constricting task of copying pictures...