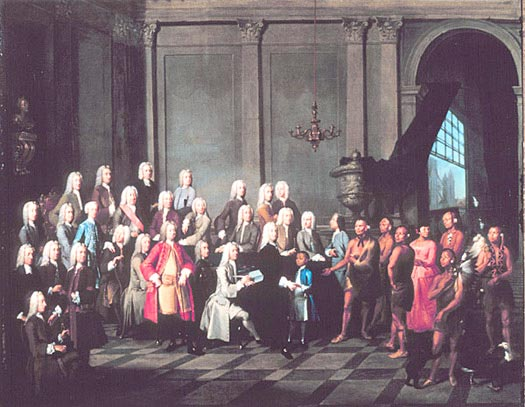

In 1710, in the reign of Queen Anne, four leaders of the Native North American Indian alliance of the Iroquois left their homeland, in what is now eastern New York State, and travelled to England. These delegates of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Mahican and Seneca peoples found themselves in a difficult position, controlling territory that was sandwiched between the English settlements, along the Eastern Seaboard of North America, and those of the French, along the St Lawrence River and the Great Lakes. They had been encouraged to come to London by the British architects of a plan to invade Canada, the purpose of their trip being to forge a mutually rewarding alliance. They made a speech to Her Majesty, expressing their hopes and intentions in phrases doubtless improved by the military planners and diplomats who had engineered their visit: “we were mightily rejoiced when we heard … that our Great Queen had resolved to send an army to reduce Canada … and in token of our friendship, we hung up the kettle, and took up the hatchet … The reduction of Canada is of such weight, that after the effecting thereof, we should have free hunting and a great trade with our Great Queen’s children: and as a token of the sincerity of the six nations, we do here, in the name of all, present our Great Queen with these belts of Wampum.”

For her part, Queen Anne graciously accepted the belts – symbols, to the Iroquois, of an unbreakable alliance – and commissioned the Dutch expatriate artist John Verelst to paint a series of portraits of the “Four Indian Kings”, as they quickly became known in England. These likenesses stand, like forbidding sentinels, at the entrance to the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition...