'It can be horrible and terrifying and beautiful and bafflinglydirect in its sheer strangeness.' Andrew Graham-Dixon on the RA's brilliant exhibition

The first thing seen in "Africa: the Art of a Continent" is non- descript but portends much. Oldowan Core, as it is described in the catalogue ("Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, circa 1.6-1.7 million years Before Present"), is said to be one of the oldest objects to show "the visible beginning of those human skills from which our artefacts and art, in Africa and throughout the world, have developed their material complexity". What looks at first sight like nothing more than a fist-sized chunk of roughened rock is suddenly charged with huge and romantic associations. The blob of stone half-formed into an almost-something by the slightest of flakings and chippings is to be seen as a wonder: the visible embryo of all human civilisations.

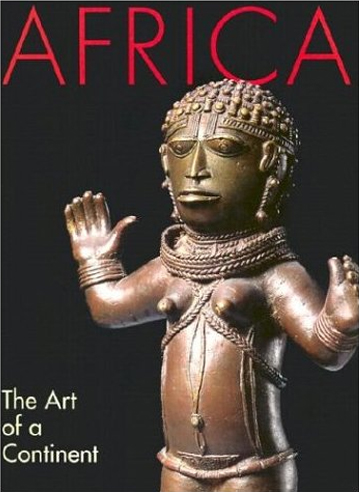

The art of a fair number of those civilisations has been crammed into 10 rooms at the Royal Academy. The curators of "Africa", Tom Phillips and Norman Rosenthal, are entirely unapologetic about the necessary sketchiness of the picture this paints of an entire continent's visual culture. Phillips, who hopes to honour the Royal Academy's tradition of "enlightened foolhardiness", writes of the show in its tombstone catalogue that it is "a sampling of the art of an entire continent" - a phrase bound to raise questions and eyebrows. A "sampling" of the art of a thousand thousand different cultures, drawn from all over one of the largest land masses on the surface of the globe, with a time-span that stretches back from 20th-century South Africa (pierced wooden earplugs) all the way to ancient Egypt (an almost unbearably erotic stone statue of Nefertiti wearing a body-hugging prototype of a Fortuny outfit) - and back, still further back, into the...