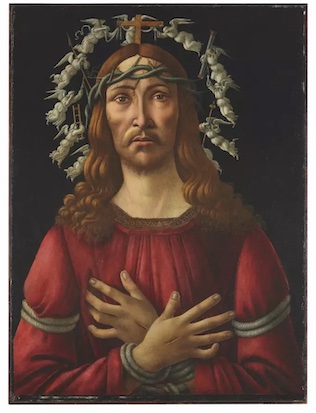

Sandro Botticelli's The Man of Sorrows is a stark and haunting picture. Dating from around 1500, at first glance it looks like a bust-length portrait painted from life. But since the subject is someone not seen in the flesh for a thousand years and more, it cannot be that and must be taken for a vision. I suspect that this uneasy blend of the imaginary and the real is part of Botticelli's meaning: his way of declaring that salvation lies in the same act of empathy that has made a picture such as this possible. If you can make Christ so present, in your heart and soul, that he might be standing in front of you, then - and only then - might you be saved.

Christ is clothed in red, the colour of blood and the colour of his Passion. He is so tightly bound he can barely move. Ropes cut into his wrists and his arms. He wears a crown of thorns as fat as a snake. Blood trickles down his forehead and into the cavity of his right eye. His head is haloed by a troupe of tiny dancing angels, who are armed with the instruments of his Passion: the scourge; the lance; the column to which he was bound; the vinegary sponge with which he was mocked; the cross itself.

The signs of his suffering are everywhere about him, most subtly in his eyes, where compassion is mingled with smouldering anger. He is Christ the Judge as well as Christ the Saviour. It is easy to imagine him casting off ropes that bind him, raising his right hand to bless the saved, lowering his left to condemn the damned. This is not a picture that invites you to stand in front of it...