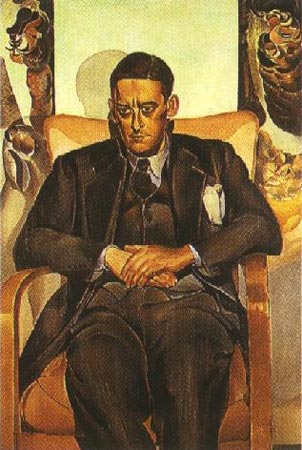

Percy Wyndham Lewis had a talent for making himself unpopular. He enjoyed making enemies and courted controversy at every twist and every turn of his tortuous career as painter, novelist, satirist, cultural critic and political demagogue. His opinions were as volatile as his temperament, and he generally made sure that they flowed against the tide of the consensus view. One minute he was playing devil’s advocate for Hitler and the National Socialists, the next – having taken the trouble to go and see what was actually going on in Berlin – he was fulminating against the Nazis and cursing Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement. A master of caricature, Lewis was himself easily caricatured – as racist and misogynist, Fascist and homophobe – but not so easily pigeonholed. He was especially detested by the Bloomsbury set, whom he attacked mercilessly at every opportunity, but such loathing was by no means confined to the British Isles. Ernest Hemingway memorably wrote of him that “I do not think I have ever seen a nastier-looking man. Under a black hat, when I had first seen them, the eyes were those of an unsuccessful rapist.”

Lewis’s mutable persona was more than merely rebarbative. It was in itself a kind of work of art – a form of avant-garde statement, an idiosyncratic and carnivalesque means of insisting on the fluid, contradictory nature of reality. His ideas influenced writers as diverse as the father of modern media studies, Marshall McLuhan, and the poet W.H. Auden (who once described him as “that lonely old volcano of the Right”). Lewis was a true modernist, in the sense that he lived out the sense of fractured reality described both by Cubist painting and the restlessly experimental literature of the early twentieth century – the poetry of Eliot and Pound, the...