In 1925, Punch published a caricature of the famously fluent and, by the standards of the time, fabulously wealthy painter William Orpen. The anonymous cartoonist showed the grimacing artist, poised with his brush as if it were a fencing foil, above a short caption in rhyming couplets: "Bill Orpen's rapier thrust is great; He'll paint your portrait while you wait; But, though he doesn't want it known, He much prefers to paint his own."

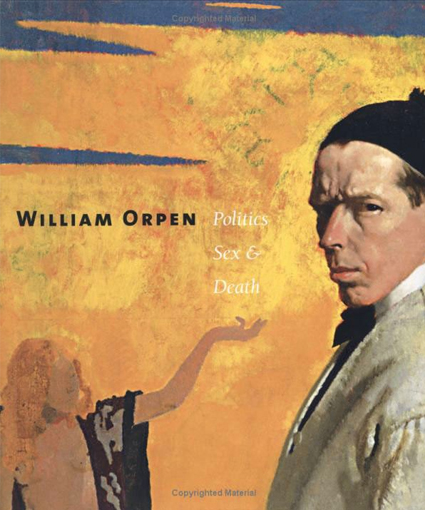

William Orpen: Politics, Sex and Death, at the Imperial War Museum (until May 2), is the latest in a series of recent exhibitions intended to resurrect the reputations of formerly eminent Edwardian painters. The show comes hard on the heels of Tate Britain's distinctly uneven survey of the art of Augustus and Gwen John, and of the Royal Academy's modest but rather more impressive display of the work of William Nicholson. Sale-room prices for Orpen's pictures, having long stagnated, have shown a marked increase in recent years. In the words of curator Robert Upstone, "Orpen's first exhibition in a British national museum will hopefully continue his rehabilitation and reevaluation."

Whatever else the exhibition achieves, it certainly demonstrates the justice of the jibe concocted by Punch's satirical versifier. Few British painters have ever been so preoccupied with their own self-image as Orpen. The Imperial War Museum show opens with a veritable cornucopia of the artist's self-portraits, executed in a baffling mixture of styles, showing him in all kinds of poses, playing a bewildering variety of different roles. The earliest of these pictures, The Nell Gwynne Public House, was painted some time between 1898 and 1904, in a deliberately drab and dingy manner seemingly indebted to Sickert and early Van Gogh - although there are faint echoes, too, of Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergeres. It shows Orpen...

William Orpen: Politics, Sex and Death, at the Imperial War Museum (until May 2), is the latest in a series of recent exhibitions intended to resurrect the reputations of formerly eminent Edwardian painters. The show comes hard on the heels of Tate Britain's distinctly uneven survey of the art of Augustus and Gwen John, and of the Royal Academy's modest but rather more impressive display of the work of William Nicholson. Sale-room prices for Orpen's pictures, having long stagnated, have shown a marked increase in recent years. In the words of curator Robert Upstone, "Orpen's first exhibition in a British national museum will hopefully continue his rehabilitation and reevaluation."

Whatever else the exhibition achieves, it certainly demonstrates the justice of the jibe concocted by Punch's satirical versifier. Few British painters have ever been so preoccupied with their own self-image as Orpen. The Imperial War Museum show opens with a veritable cornucopia of the artist's self-portraits, executed in a baffling mixture of styles, showing him in all kinds of poses, playing a bewildering variety of different roles. The earliest of these pictures, The Nell Gwynne Public House, was painted some time between 1898 and 1904, in a deliberately drab and dingy manner seemingly indebted to Sickert and early Van Gogh - although there are faint echoes, too, of Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergeres. It shows Orpen...