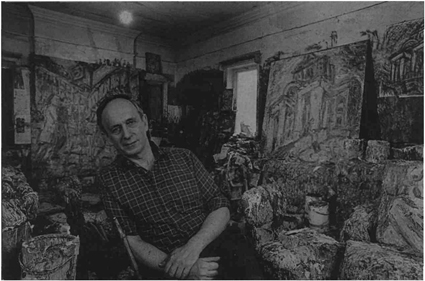

In his first interview for many years the painter Leon Kossoff talks to Andrew Graham-Dixon about his work

FORGET topography; when Leon Kossoff paints Christ Church, Spitalfields, architec¬ture turns fantastical. Painted broadly in a range of greys and offwhites, the pigment so heavily worked in places that it gathers in thick, impasted snowdrifts, Kossoffs Christ Church is an eminence grise, shouldering its fabulous, pillared and pedimented bulk into a turbulent sky.

There are distant echoes of Van Gogh. The building shudders under a weight of emotion. At odds with its Portland-faced solidity, Kossoffs church seems more animate than architectural, heaving at its own structure, threatening to come apart at the seams, to topple out of the churning heavens. In the foreground, dwarfed, cursory figures await the outcome. There is additional drama in the flickering skein of dribbles, flicks and spills that plays over the whole image; detached from description, Kossoffs paint becomes an index of excitement.

Christ Church, Spitalfields, Summer 1987 is one of 42 paintings in Kossoffs new exhibition at Anthony D'Offay Gallery. There is enough, in this one work, to question the old, narrow view of Kossoff, as East End Existentialist — the gloomy meditator on futility In whose dark, clotted paintings of the 1950s John Berger (setting the tone for subsequent interpretation) found "pro-found pessimism", "hatred of sensual pleasure" and a "belief in the equality of hopelessness".

The picture breathes a sense, not of pointlessness, but wonderment. The impulse to paint Hawksmoor's great church came, Kossoff recalls, "from reading the first few chapters of Peter Ackroyd's novel, Hawksmoor, which reminded me of my own childhood in Spitalfields. I must have passed the church five or six times a week; it did have a strange, terrifying feel about it, yet at the same time it was marvellous."

Over...