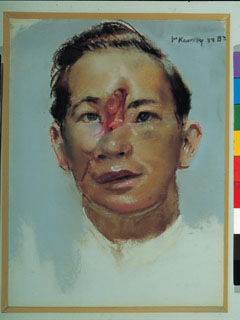

When the First World War was at its height Henry Tonks, Professor of the Slade, found himself serving in the Medical Corps of the British Army. Although qualified as a surgeon, he was an artist by profession, painting landscapes and portraits in a fluent, accomplished, conservative style that owed much to the example of French Impressionism. His wartime duties also required him to paint portraits, albeit of an unusual kind. As part of his work in the “facial reconstruction” unit, he depicted the terrible wounds suffered by young soldiers at the front. He painted men without ears and noses, or with tongues lolling from holes where their jaws had once been. He painted faces burned so badly they had become little more than two eyes staring from an amorphous mess of livid, crimson flesh.

The resulting pictures are among the most moving visual documents of the Great War, full of pathos yet also touched by a deep irony. They are the work of an artist who had little time for the avant-garde movements of his day, an artist who detested the likes of Picasso but who found himself, nonetheless, forced by a terrible reality to paint pictures resembling nightmarish modernist visions – faces melted by fire into screaming Expressionist masks, faces rearranged by shrapnel and shot into living Cubist collages. Each image is labelled with dispassionate rigour – Disfigured Soldier Number 18 – although the artist’s fellow-feeling for his traumatised subjects is painfully apparent. There was no surgical requirement to capture their expressions, but he did so nonetheless. The look in the young men’s eyes is desolate, desperate, trapped.

Tonks’s pictures are owned by the Royal College of Surgeons and infrequently exhibited. “War and Medicine”, a free exhibition currently at the Wellcome Collection, offers the rare chance to see...