Andrew Graham-Dixon on artists copying other artists

"GENIUS," wrote Sir Joshua Reynolds, "is the child of imitation." You only need to look at his portraits to sec what he meant: Reynolds would happily kit out an English milord in the borrowed grandeur of a Titian monarch, or dress up some well-to-do couple like a Juno and Jupiter courtesy of the School of Bologna. His contemporaries admired him for it — he was, in their eyes, continuing a noble tradition. Since then, a host of "isms" has intervened. Imitation and tradition have become dirty words; geniuses are supposed to be, above all, original.

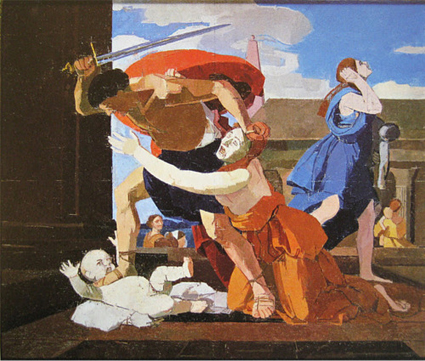

The spirit of Reynolds hovers, unfashionably, over much of the "•work in a new exhibition at Manchester City Art Galleries. Copying from the old masters was, for centuries, regarded as an essential part of any artist's training: "Past and Present", a quietly polemical show which assembles a mass of copies by 15 practising British artists (working mostly from masterpieces in the National Gallery), aims to prove that it still is. Frank Auerbach, in a catalogue note to his own old master studies, comments tersely that "Painting is a cultured activity — it's not like spitting, one can't kid oneself."

Cabbies do "the knowledge"; artists — at least the older, figuratively inclined British generation represented here — make copies. This is very much a nuts-and-bolts show, offering a series of artists' insights into How Masterpieces Work: the ways and means of composition (formal checks and balances, the well-managed horizontal or vertical), the handling of tone, the expressive tilt of a head or disposition of a figure. Francis Hoyland picks up a compositional hint or two from Frans Hals' great Family Group in a Landscape: Hals's busy group, thronging with anecdotal detail, is reduced to bare, linear essentials, its figures...