Sculpture has undergone a renaissance. Andrew Graham-Dixon on new developments

TONY CRAGG'S Contained Reaction, at the Hayward Gallery, looks like a lament for the age of science — a monumental work conceived, cussedly, in an era that has ceased to believe in the monumental functions of sculpture.

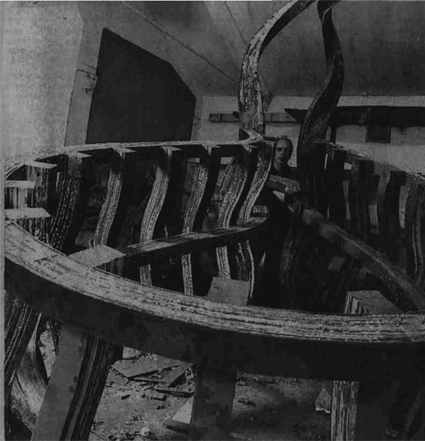

Cragg's massive oddments, cast in heavy sheet steel and dusted sensually with the bright orange patina of rust, look as though they have been deposited, centuries ago, by an absent-minded scientist from Brobdignag. Two massive long-necked phials are flanked by vast, hulking test-tubes moulded from the same opaque rusted steel, long since emptied of the substances that might have been tested in this mysteriously abandoned experiment. One of these tubes has been distorted by heat, so that it snakes sinuously around the front edge of the ensemble, implying (the leitmotif of Cragg's art) the volatile, unstable nature of matter, the metamor-phic properties and metaphorical resonances of all that stuff which we call, collectively, "the world".

Cragg is one of a number of young(ish) artists who have been grouped under the banner headline "New British Sculpture". Between them, they are having a busy month (see below).

"A Quiet Revolution" is how the large show of new British sculpture now touring America announces itself, with a mixture of characteristically British self-effacement and genuine accuracy. It has been a quiet revolution, especially when you consider the context in which all these sculptors developed. None came to prominence until the early Eighties, when all the excitement surrounding the so-called "return to the figure" in painting — which had most artists hurriedly ditching abstraction, minimalism and conceptualism and flexing their Jungian subconsciouses in public — was beginning to look, with few exceptions, like so much hype.

When it was unfashionable to be working as a sculptor at all,...