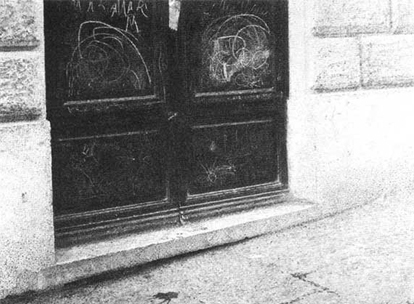

RIGHT AT the start of the Royal Academy's whirlwind tour of 'Italian Art in the Twentieth Century', you come across a small, unassuming picture painted by Giacomo Balla in 1902, titled Bankruptcy. Rendered in a light drizzle of Divisionist brushmarks, its subject is, on the face of it, nothing much - a pair of closed doors set into a facade of heavily rusticated, honey-coloured stone. No people are included, so all the eye can do is take in the dull, urban details that Balla's brush has dwelt on - the wriggling graffiti that deface these barred doors, the indeterminate stain that marks the pavement before them.

Yet Balla's painting has a kind of downbeat, generic potency. Thisfaded, timeworn excerpt from Italian urban existence at the turn of the century is, still, quintessentially Italian - an image of dusty, creeping decay of precisely the kind that you might encounter in any Italian town today. It is a reminder of Italy's stubborn rootedness in the past, of its inability - notwithstanding the efforts of the likes of Alitalia and Fiat, joint sponsors of this exhibition - to be wholeheartedly, technologically modern.

There is, inevitably, something inherently suspect about any attempt to find evidence of national identity in a country's art. But this exhibition mounts an extremely convincing case for what it sees as the Italianness of Italian art - arguing that Italian art has always been peculiarly attracted or repulsed by the idea of the past.

The ghost of history, that haunts even Italy's most modern cities, turns out to be both modern Italian art's bane and its driving force. The show starts with a bang, its opening room given over to the Futurists, whose manic embrace of modernity puts a brave face on Italian art's perennial, neurotic sense of...