Andrew Graham-Dixon on the major new exhibition at the Grand Palais, Paris

Paul Cezanne, the dyspeptic hermit of Post-Impressionist French painting, has been widely claimed as the patriarch of modern art. It has become almost conventional to view Cezanne as the founding father of a new, 20th-century way of seeing and thinking about the world - an artist whose achievements went beyond art, into science and philosophy.

"Masterer of reality" was how the poet Rainer Maria Rilke described him, writing in 1907, a year after Cezanne's death. But was Cezanne truly the Einstein of painting? The large retrospective of his work, currently to be seen at the Grand Palais in Paris, later to arrive in London, leaves the question open.

The Cezanne on view in Paris is not quite the unruffled philosophic genius of modernist reverence - a figure who has, incidentally, quite a lot to answer for, certainly in this country, including thousands upon thousands of appalling student paintings of themes such as "The Faceted Apple", almost all the works of the Euston Road school, and the plumbline-and- squint method of drawing still being taught, remarkably, in certain British art schools today. The Cezanne on view in Paris is instead a complicated, uneasy figure, driven by anxiety as much as anything else.

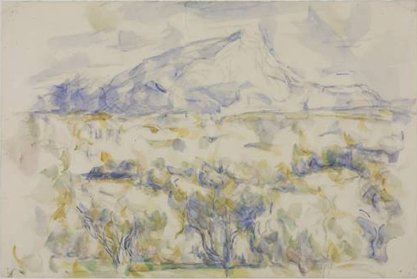

The sheer scale of this exhibition has a necessarily humanising effect on its subject, revealing his weaknesses and oddities and the extent to which he had to struggle with the refractory nature of his own personality. Among other things, this serves to clarify the twofold paradox of Cezanne's position in the history of art: first, that someone who spent virtually his entire creative life rooted in a tiny patch of Provencal countryside should have come to be regarded as the pioneer of the first great urban 20th-...