James Turrell's lucid and beautiful art is hard to describe because it consists of almost nothing: a few partitions erected inside the gallery, light or its absence, and the way those things relate to one another. ''James Turrell'', at the Anthony D'Offay Gallery, is his first significant one-man show in this country. He has used the occasion, you might say, to demonstrate his light touch.

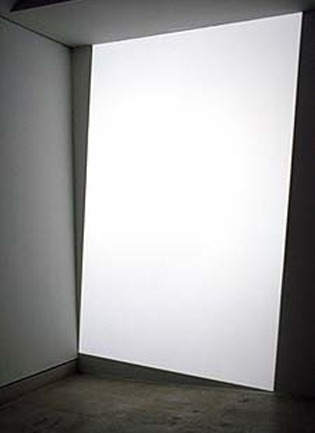

Rayzor, which occupies (or, more accurately, transforms) the largest of several galleries at Anthony D'Offay, is a hypnotic example of the effects Turrell manages to derive from simple means. At first, you have the impression that you are looking, simply, at a large, bluish rectangle attached to the gallery wall. Then you realise that the wall which surrounds it is no such thing - that the white border that defines its edges is made of nothing more substantial than light, leaking around its sides from behind. Moreover, this light has been regulated in such a way that it makes that blue rectangle appear to hover in space, to shimmer and on occasion dissolve, almost dematerialising before your eyes. Its colours also change, on prolonged examination, in response to the character of the daylight outside the gallery, so that in late afternoon what was light blue darkens, or develops a violet tinge, or seems to pulse and vibrate.

Knowing that it's all done with lightweight aluminium and fluorescent light does not diminish its effectiveness. Turrell's art can sound gimmicky, when you get into the nuts and bolts of it, but its success is in large measure due to the way in which he suppresses awareness of the technology that has gone into the creation of his subtle illusions. The apparatus is hidden, rendered utterly unobtrusive, so all that counts is the visual experience which it makes...