'His life was, among other things, a prolonged act of metaphorical patricide': Andrew Graham-Dixon re-views 'Dali: The Early Years'

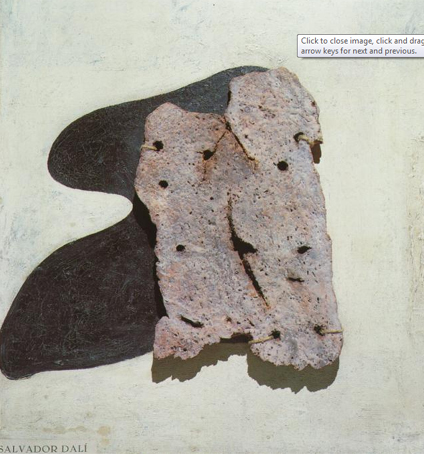

Salvador Dali was a teenager when he painted his Portrait of My Father, a picture which cannot help looking, in retrospect, like an allegory of classic teenage Oedipal angst. Dali senior, in a sober suit, is a dark colossus looming over the bright city and sea and distant hills of Cadaques, a Spanish fishing village which the young Dali has painted, here, as a garish Fauve idyll. The sheer bulk of father is what strikes son: he sees his father as an enormous black silhouette, a blot on his landscape.

''Dali: The Early Years'', at the Hayward Gallery, might have been expected to furnish many such portents, indicators of the fruitful unease necessary to one seeking a career in Surrealism. Surrealism was dedicated to the discovery and expression of primal (preferably Freudian) trauma, to the guiltily transgressive child within. A Surrealist's juvenilia ought to be especially revealing, since the theory of Surrealism reverses the traditional momentum of a career and argues that the artist should not seek to move on, but to regress to the dangerous, radically uncivilised condition of the infant. But the hitherto unexplored territory of Dali's early work turns out to be disappointingly barren in this respect.

The chief revelation here is how canny and cold-blooded, how thoroughly in control of himself Dali was from an early age. The young Dali was a magpie-like stealer of other artists' styles. The willed Fauvism of his Portrait of My Father gives way easily and simply to the willed Symbolism of his Portrait of Grandmother Anna Sewing, painted later in the same year, a blue and misty murk which pictures an old woman patiently sewing in a room that looks as...