“The American Scene: Prints from Hopper to Pollock”, at the British Museum, shows America as it was reported, recorded, imagined, satirised and celebrated by American printmakers during the first half of the twentieth century.

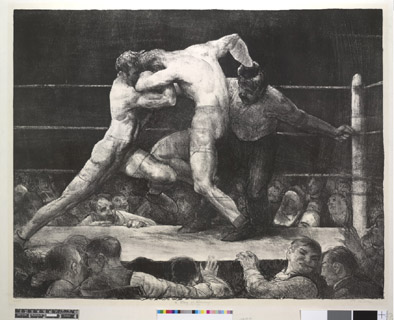

This small but muscular exhibition opens punchily with George Bellows’ A Stag at Sharkey’s of 1917, which was inspired by the illegal prize fights that used to take place at Tom Sharkey’s Athletic Club on Broadway in Manhattan. The audience for such events consisted entirely of men – which is why they were known as “stags” – and Bellows gives as much attention to the casual, smiling, voyeuristic sadism of the male onlookers as he does to the sweaty grapplings of the boxers themselves. The pugilists are entangled like a pair of damned souls bound to one another forever, while the watching referee, arms outstretched, evokes a man being crucified. An inky lithhographic darkness enshrouds all.

Bellows was a prominent member of the Ashcan School, so named for its resolute determination to capture the gritty, brutal and often squalid reality of life in the big American cities during the early decades of the twentieth century. The Ashcan artists were America’s answer to the French “painters of modern life”, who had been summoned into being by the poet Baudelaire’s clarion call for an art of the modern metropolis. Like Manet and Degas and the other masters of late nineteenth-century French painting, the Ashcanners depicted city experience as a series of fractured, snapshot glimpses and glances.

But there was more to them than a late, transatlantically transplanted version of Impressionist style. For his part Bellows was looking back, beyond Impressionism, to the Spanish artist whom he considered to be the first and most radical of the “moderns”: Francisco de Goya. Bellows’ A Stag at Sharkey’s, the...