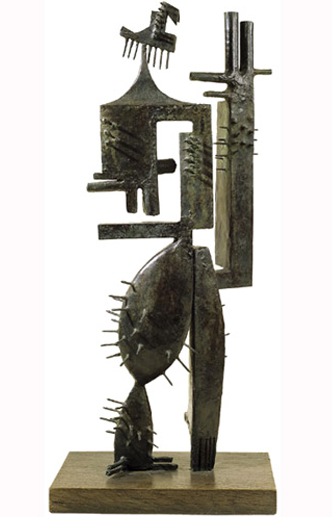

Andrew Graham-Dixon on fragile constructions by Julio Gonzales, and Glasgow's Great British Art Exhibition

THE CHANCES are that no one would have heard of Julio Gonzalez if Picasso hadn't gone looking for him in 1928. Picasso had some ideas for welded metal sculpture but, lacking an oxyacetylene torch and the relevant technical know-how, he needed help. Gonzalez, a fellow Catalan, had the right qualifications: a background in one of the most famous metalsmiths' workshops in Barcelona and work experience on the Renault production line.

Over the next three years, Gonzalez helped Picasso to make six metal sculptures, the most famous of which is the Head of a Woman now in the Musee Picasso in Paris - a composite maenad, concave dish of scrap metal for a face, paired colanders for a cranium, dangling bedsprings for hair and half a door hinge, minus its screws, for eyes. Gonzalez was sufficiently impressed, the story goes, to request Picasso's ''permission to work in the same manner as himself''. Flattered, and perceiving no threat from this diffident metalworker already in his mid-fifties, Picasso granted it. For what happened next, consult ''Julio Gonzalez'' at Glasgow City Art Gallery and Museum.

Gonzalez, never easy to categorise, has been filed away under S for Surrealism and, more commonly, under P for Picasso (footnote to). There is as strong a case for putting him under C for Cubism, which rests on the series of masks and busts he made in the early 1930s, among the first works you see in Glasgow. Gonzalez's masks, sheets of metal into which the artist has cut and folded basic facial details like eye or nose, represent a late but elegant reworking of Cubist ideas: complex, shifting forms that are, thanks to the nature of their construction, peculiarly variable according to the lighting...