Andrew Graham-Dixon reviews landscapes from nature and their man-made competitors

WITH Anselm Kiefer at the Saatchi Collection and Julian Schnabel at the Whitechapel some of the finest and most controversial painting of the last ten years is currently on view in London. It is a tough double act to follow, but Ian McKeever — whose breathtaking show opened at Nigel Greenwood on Friday —has come up with work that rises to the challenge.

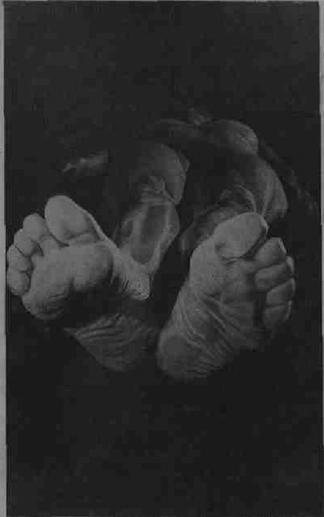

McKeever admits to great admiration for Kiefer's work, and like him is a painter of superb landscapes in the Northern Romantic tradition. McKeever country is as dark and Germanically desolate as any Kiefer landscape, a land of mountains, glaciers and torrents, haunted by mists that fall and rise with mysterious and omi¬nous unpredictability. Like Richard Long (also showing new work in London this month) McKeever is one of modern art's solitary walk¬ers — all the paintings in the show derive from a two-month hike around Lapland last summer. Also like Long, he makes extensive use of pho-tography. But where Long affixes suitably mini¬mal inscriptions to his photographic pieces ("A Line Made by Walking"), McKeever physically assaults the photographs in his own work. He enlarges his black and white snapshots of bleak Nordic wastes and rotting primeval forests, fixes them to large canvases and then proceeds to bury them under avalanches of oil paint.

McKeever has a magnificent grasp of painting in its most fundamental, bodily form — as rhythm. Fragments of his original photographs remain visible, but they are obscured by vigor¬ous calligraphic swirls, smudges and smears of paint. He gives paint the fluidity of natural pro-cesses — etherising to mist (in the mountain and glacier paintings) or coiling vegetatively into busy, root-like structures (in the forest paintings).

Only seven or eight years ago, McKeever did not...

Romancing the rocks and stones and trees

20-11-1986