In 1898, in one of his conversations with Joachim Gasquet, the painter Paul Cezanne turned for a moment to the subject of Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), then regarded as the greatest sculptor of the age. Cezanne, who viewed Rodin as an astonishing enigma, remarked that “No one knows what he is really like deep down. He is a Man of the Middle Ages who does make great pieces, but he doesn’t see the whole. He needs to be framed, like these old sculptors, in the portal of a cathedral.”

The Royal Academy’s dizzying new exhibition of Rodin’s sculpture attempts to frame the artist’s achievement, with due reverence, in a suite of ten galleries. The tall and elegant rooms of Burlington House have been given over to some 200 of his works – sculptures, working models, fragments and numerous sheets from his huge, lifelong outpouring of drawings – although they cannot quite be said to contain them. The work seethes rather than rests in space and gives the constant impression of overflowing the rooms that house it.

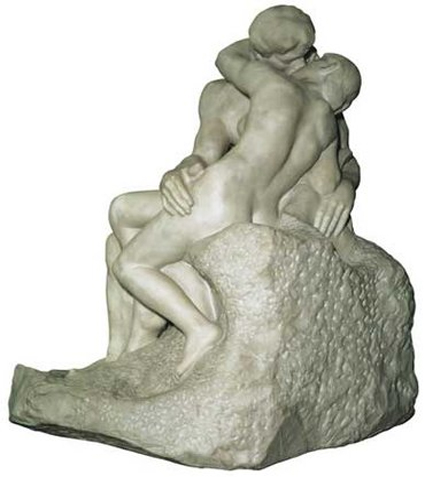

Rodin’s figures stretch and gesticulate, swoop and fall, rapt in the mystery of their own being. Even when simply thinking, they are possessed by a restless energy, communicated not simply by pose but by the living surface given to his every form by the sculptor’s hands. The sinews and muscles of Rodin’s figures in bronze seem to vibrate, as if to convey the belief that flesh itself might express the uneasy movements of the mind. The roughened plaster of his maquettes shivers and vibrates, so that even the air around the sculptures is animated by their potential motion. If Cezanne was correct in his belief that Rodin “doesn’t see the whole”, it is also true that Rodin continues to elude attempts to see...