Some of the most rewarding events at the National Gallery are its smaller exhibitions, when the museum borrows a few works from elsewhere, sometimes just one or two, because they shed new light on those already in its permanent collection. Standing at the opposite end of the exhibition spectrum from the lumbering circus elephant that is the museum blockbuster, such shows rarely attract the attention of reviewers. This appears, so far, to have been the misfortune of the tremendous display of paintings from the early period of the career of Peter Paul Rubens currently occupying Gallery 29 at Trafalgar Square.

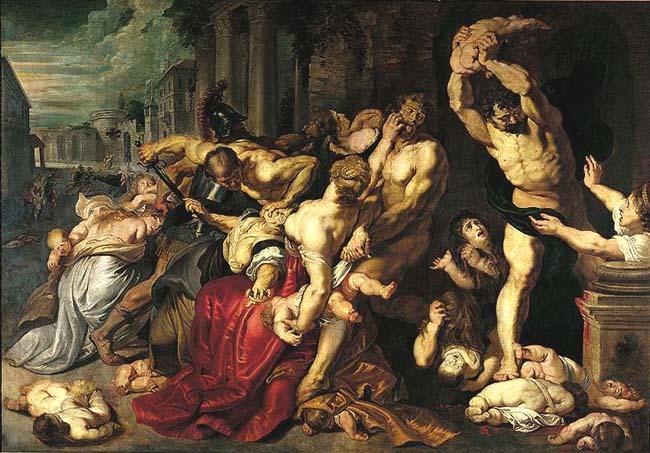

Subtitled “The Making of an Artist”, the display focusses on a handful of works (essentially three masterpieces, together with supporting pictures) created by the painter in his early thirties. They are among his most dramatic, bloody, sexy, muscular creations. All were forged in the white heat of his youth; but what makes the works in question all the more remarkable is the fact that two of them have been recently rediscovered after centuries of neglect, while the third has only now gained universal acceptance as a genuine Rubens. Between them, they transform the previously hazy picture that had existed of Rubens’ early maturity and make it possible to see the emergence – like that of a butterfly from a chrysalis – of his genius.

The National Gallery is an appropriate venue for this display because 20 years ago its trustees had the courage to purchase Rubens’ disputed masterpiece Samson and Delilah for the bargain basment price of £2.5 million. Questions were asked about the authorship of that painting, largely because it differed so assertively from Rubens’ few other known works of circa 1609-12, in its tenebrous light and its sculptural treatment of human anatomy. Since then the near-miraculous emergence of...

The National Gallery is an appropriate venue for this display because 20 years ago its trustees had the courage to purchase Rubens’ disputed masterpiece Samson and Delilah for the bargain basment price of £2.5 million. Questions were asked about the authorship of that painting, largely because it differed so assertively from Rubens’ few other known works of circa 1609-12, in its tenebrous light and its sculptural treatment of human anatomy. Since then the near-miraculous emergence of...

Review of “Rubens Display” at the National Gallery

11-01-2004