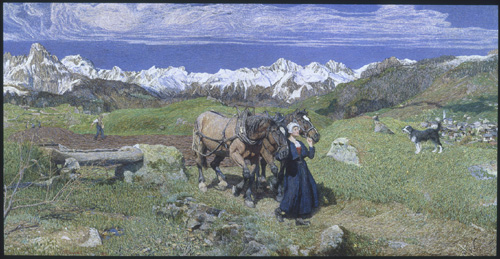

“Radical Light”, a vividly disparate exhibition of early modern Italian painting at the National Gallery, opens with a clutch of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century landscapes. The accent is on wildness, or at least pastoral remoteness. Emilio Longoni perches the viewer on the brink of a yawning crevasse in a glacially white world. Giuseppe Pellizza depicts a solemn procession of funereal villagers, on their way to a country church to bury a dead child. Giovanni Segantini’s Spring in the Alps, a spectacularly ambitious panorama of life in the mountains, is a joyful counterbalance to such fin-de-siecle morbidities. Against a backdrop of snow-capped mountains and a sky of radiant blue, a farmer sows a fresh-ploughed field of dark red earth with generous handfuls of seed. In the foreground a stout alpine maid leads a pair of plough-horses to pasture, while an alert black and white dog looks on with the air of a contented foreman approving a job well done. All is well with the world and God is in his heaven.

The subject of Segantini’s painting, a natural idyll, is hardly exceptional in late nineteenth-century art, but his style is arresting and idiosyncratic. He had read Michele-Eugene Chevreul on the effect of complementary colours and he was familiar with Ogden G. Rood’s influential Modern Chromatics of 1879, a detailed study of colour contrasts and harmonies rooted in an analysis of the properties of light. Like his famous French predecessor, Georges Seurat, inventor of Pointillism, Segantini was inspired by such theories to paint in a new style. He applied pure colours in fields of tiny strokes of complementary colours, to create the effect of coloured light merging to create an image on the human retina. But whereas Seurat had favoured the discrete dab or dot, Segantini painted in...