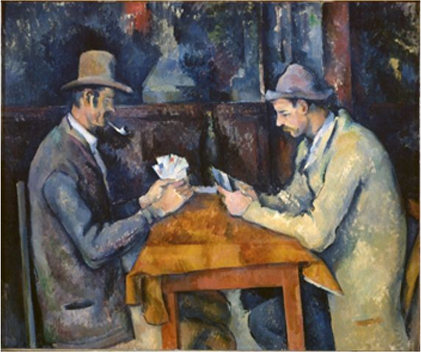

“Cezanne’s Card Players” at the Courtauld Gallery.

The Courtauld's new Cesanne exhibition reveals the artists fondness for a gentler age in the face of bounding industrialisation.

Theodore Duret, one of the most passionate advocates of Impressionism, described his friend and contemporary Paul Cezanne as the ascetic founding priest of a new order of painting: “Having become rich, he changed nothing of his way of life. He continued as before, painting assiduously, never taking interest in anything except his art. The years seemed to go by while leaving him isolated.” Cezanne was unlike all previous artists, Duret believed, in that he painted purely according to the dictates of his own drives and sensibilities. Oblivious to inherited conventions of subject matter or technique, ignoring even the most fundamental shared systems of perspective, he freed himself to see the world in a completely new light: “He paints because he is made for painting... He paints solely for himself.”

Like most myths, it contains a grain of truth. Cezanne was indeed an extreme innovator, a man of piercing intelligence and thrusting iconoclastic energy who set out to reinvent the painting of his time. Having understood that nineteenth-century art was in the throes of wrenching change, he did his utmost to accelerate it. He saw, more clearly perhaps than any of his contemporaries, that the prevailing placid conventions of academic art were under assault from two opposing avant-gardes. Each had its origin in England. On the one hand there was the raw emotionalism of the Romantic movement, led by John Constable’s battlecry that “painting is but another word for feeling”– a strain of pictorial innovation taken up and developed, in France, by Gericault and above all Delacroix, with his almost orgiastically expressive sense of gesture, texture, colour. On the other hand, there was what...