Andrew Graham-Dixon on an exhibition of oversized and vacuum-pácked constructions by sculptor Julian Opie.

A few years ago, when he was Britain's Most Promising Young Sculptor, Julian Opie seemed to have everything going for him. His work was zany, figurative, accessible. Blessed with an irreverent, streetwise talent, Opie couldn't fail to please.

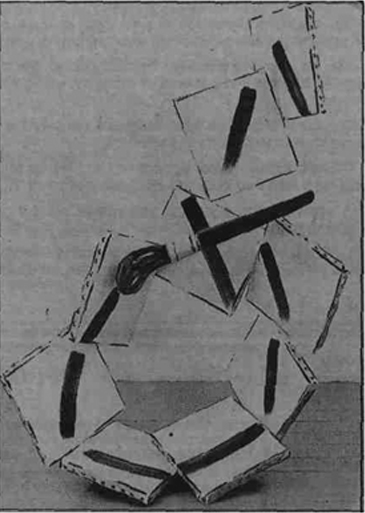

Every one of his impudent, gravity-defying constructions — made, origami-fashion, from folded and painted sheet steel — came complete with punchline. This One Took Ages to Make was a crazily suspended typewriter spewing out sheets of paper that seemed, impossibly, to flutter in mid-air. Clean Abstraction was a knowing parody of a David Smith rod;cube-and-ball abstract, comically assailed in Opie's ensemble by an army of cleaning implements — dustpan and brush, squeegee mop, trusty household-size bottle of detergent. This was art as spring-cleaning; a breath of fresh air in the stuffy, self-regarding world of contemporary sculpture.

Everyone got Opie's jokes. Almost everyone laughed. But when the laughter died away, the odd dissenting voices began to be heard. This sort of thing was all very well, and no one doubted Opie's wit or technical precocity — but wasn't it all just a bit superficial? Opie had made it to the top of the Lightweight division, but surely he would never be a real con¬tender. The doubts were even shared by some of his stablemates at the Lisson Gallery: in the catalogue to his 1985 exhibition there, Art & Language (the con-ceptualist double-act of Michael Baldwin and Mel Ramsden) noted their fear that he might merely turn out to be "British artsy-crafty", the producer of "romper-room furniture" or "executive jewellery".

It all seems to have got to Opie. Take his current show. The U-turn, apparently, has been completed. Jokes have gone to the wall. So, too, has most of the...