It has been clear for a while now that Sir Anthony Caro, alias ''Britain's most distinguished living sculptor'', is going through some kind of crisis. Not that production in Caro's Camden Town studio has showed any signs of slowing down. There are now said to be 2,500 of his sculptures in existence: it is going some, over a 30-year career, to sustain creativity at a rate of about two works (and often such large works) every week. But some of the most recent additions to the Caro oeuvre are, to put it politely, rather eccentric; and Caro's very productiveness - he is surely among the most prolific sculptors of the century - may in itself contain a clue to the nature of his problem.

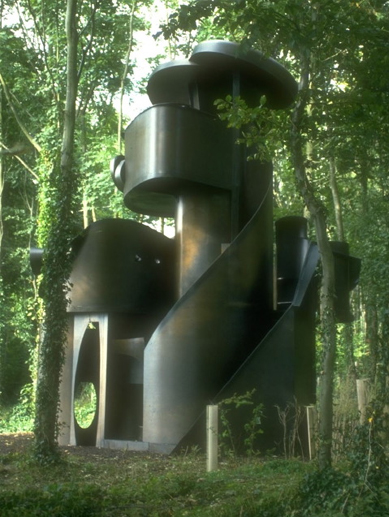

Caro's choice of medium, the metal assemblage, was famously grounded in a rejection of the principles of modelled or carved sculpture. It represents, or has always been held to, a reproof to both the monumental and the symbolic aspirations of the grand tradition of classical statuary, which might be said to extend from the art of Helenistic Greece to that of Michelangelo, Rodin and Henry Moore (whose assistant Caro once was, briefly in the early 1950s). Caro has long been the principal torchbearer of a notion of sculpture as itself and nothing but; he has been a constant discourager of metaphorical or symbolic or indeed any kind of non-formalistic interpretations of his abstract works. Yet the sheer size of Caro's output and, latterly, the increasing scale and monumental ambitiousness of his art, suggest a kind of unhappiness, a discontent with the consequences of his own devotion to abstract literalism. He has come to seem like an artist at odds both with his time and with his language: an abstractionist fatally touched by nostalgia for the very...