Andrew Graham-Dixon on putting a name to a canvas

JULIAN Schnabel's modestly titled painting, Portrait of God, is an abstract explosion of blue paint on a dirty grey piece of unprimed tarpaulin. "How can a great blue blob be a portrait of God?" Schnabel was asked by an aggrieved visitor to his recent retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery. "Why shouldn't it be?" he countered with characteristic confi-dence. "Do you know what God looks like?"

It was a smart response, but Outraged of Whitechapel did have a point. Modern art has a reputation for being obscure, and artists' titles must take some of the blame. Confronted by the frequently enigmatic manifestations of contemporary art, our natural response is to seek illumination from the gallery label. Most people are familiar with the rising sense of frustration when it turns out to be about as helpful as a straw to a drowning man.

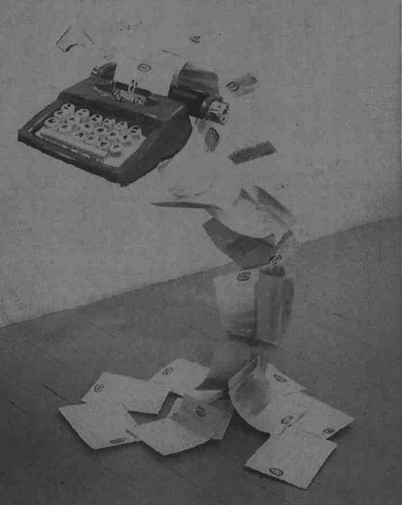

In the words of Howard Hodgkin, "giving a picture its title is the last brushstroke that the artist makes." When an artist names a paint¬ing, he does so with the responsibility (or irre-sponsibility) of a parent. Works of art, partic-ularly abstract works of art, are fickle, indeterminate creatures, unstable in all but the frozen appearances which they present to the world. One word, one scrap of verbal in-formation, can utterly change our perception of a painting or a sculpture. Were Schnabel to reticle Portrait of God he would be altering his painting as radically as if he chose to rework the surface of the canvas itself, perhaps more so.

To risk a grand generalisation, there are four ways in which an artist can title his work, like mediaeval man, he has his humours: he can be Literal, Metaphorical, Comical or (perversely) Whimsical. When I talked to Ste¬phen Buckley a few...