Patrick Caulfield died on 29 September last year at the age of 69, and was buried several days later at Highgate Cemetery. He was a convivial and generous man – both qualities are radiantly manifest in his art – and he and his widow Janet Nathan had arranged his funeral as an exuberant, joyful send-off. As a large gathering of mourners assembled at the graveside, on one of the cemetery’s broader avenues, a jazz trio played some of the painter’s favourite tunes. Fine weather contributed to the bittersweet mood, bathing the scene in bright but already fading autumnal sunlight – an end-of-the-day light, which filtered through the trees in a way that might have pleased even Caulfield, who did not care much for the great outdoors. He was a man of few words, as he demonstrated in his monosyllabic choice of epitaph: “Dead”. The word will be carved into his headstone, in lettering of his own design.

On last Sunday evening, which would have been the painter’s seventieth birthday, a celebration of his life and achievements was held in the octagon at the end of the Duveen galleries in Tate Britain. Leslie Waddington, the artist’s dealer for almost his entire career, spoke warmly of his memories of the man. John McEwen, for many years the art critic of this newspaper, remembered Caulfield’s love of London’s pubs and restaurants, and his corresponding dislike of the countryside – “the mud museum”, as he called it. McEwan also paid tribute to Caulfield’s “purity of heart”, transmitted in his painting through an equivalent “purity of line, purity of colour and purity of intention”. Nicholas Serota, Director of Tate, remarked that two hundred years from now, when historians of late twentieth-century England want to recapture a sense of how London actually looked and felt at...

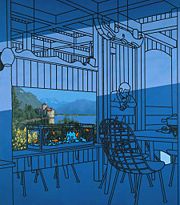

Patrick Caulfield, A Tribute Written on the Death of the Painter 2006

05-02-2006