Question: when is a painting not a portrait? Answer: when it's a Picasso. Andrew Graham-Dixon argues that, by sticking models' nameson the pictures, the new Paris show betrays the true subjects of the artist's work

The late 20th century has seen the spread of a highly infectious disease, transmitted chiefly through the medium of biography, which causes the delusion that the lives of great men and women are more interesting than their works. The organisers of "Picasso and Portraiture", an intriguing but fundamentally misconceived exhibition currently at the Grand Palais in Paris, evidently suffer from the condition.

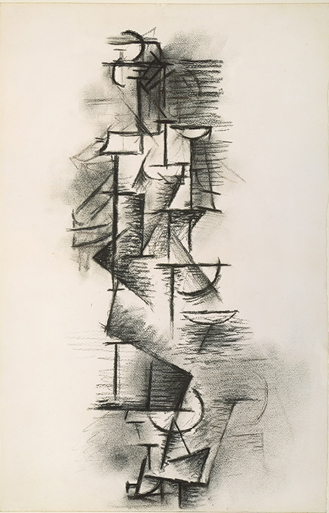

"My work is like a diary," Picasso mischievously used to say, but the remark can be taken rather too seriously. Throughout this large, ambitious survey, the viewer is encouraged to see Picasso's painting in essentially diaristic and anecdotal terms. The works on display are there to be read, indeed, as if they were pages from a journal in which the artist, as "portrait painter", obliquely noted his thoughts about himself, his family, his friends and his lovers. But to bring such literal-mindedness and such amateur detective attitudes to Picasso's art is a serious mistake. Whatever his work may happen to tell us in passing about the precise details of his life, that is the last reason to value it. His genius was inseparable from his disdain for the minutiae with which the diarist is concerned.

"Picasso and Portraiture" depends, for its very existence as an exhibition, on a shameless distortion of the truth. A great number of the works of art which it contains are, quite simply, not portraits at all. Yet they have been treated as such by the organisers of the exhibition, which means that the show as a whole tells an insidious and symptomatically modern lie about the...