THE V&A'S ''The Art of Death'' was postponed when the Gulf War broke out, presumably because it was felt that its subject was, er, a little close to the bone. But it is hard to see who could have been offended by this show, whose scholarly intent is manifest in its subtitle, ''Visual Culture in the English Death Ritual c.1500-1800''. A cornucopia of memorial paintings and sculptures, as well as many other objects of more sociological than aesthetic interest, it is an exhibition that has, itself, something of the memorial service about it. It commemorates a buried part of our cultural past, a conception of death that is, itself, dead.

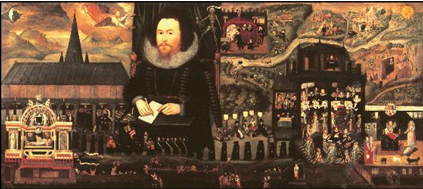

Although modern attitudes to mortality fall outside the scope of this show it does, inevitably, prompt comparisons between the way we feel about dying and the way our ancestors did. Looking at The Unton Memorial, for instance, it is hard not to see a measure of the gap between notions of death in the 1590s and the 1990s. Commissioned by Sir Henry Unton's widow at the end of the sixteenth century, the painting is both startling and alien. A memorial to the dead and an encouragement to the living, it is a work that begins to make sense of curator Nigel Llewellyn's bizarrely phrased remark, in the exhibition catalogue, about ''the positive aspects of death, as a learning process''.

Henry Unton was a British diplomat who died, in his early forties, on an ambassadorial mission to France. There are many Henry Untons in The Unton Memorial, but the largest of these figures, who stares out at you from the centre of the canvas, is the key to the nature of the painting. The pen in his hand hovers over a blank sheet of paper while, above him, hover Death with...