Andrew Graham-Dixon asks whether the contents of the Tate's new gallery live up to its exterior

AS YOU enter the impressive Albert Dock complex, prime site of what is widely being touted as the cultural Renaissance of Merseyside, you are greeted by a sign that reads "Welcome to Sponsored by Volkswagen." That, at least, is what it seems to say; on closer inspection, sandwiched between "Welcome to" and "Sponsored", and perching above the VW logo, you can just make out — in a tiny typeface of the sort normally used by oculists — the words "Tate Gallery Liverpool."

Maybe it's an appropriate introduction to the Tate's flagship in the North; it's a reminder that Britain's newest art gallery needs to be a lot of different things to a lot of different people. The Merseyside Docklands Corporation wants a sym-bol of civic renewal, and hard evidence that mod-ern art can attract business interest; the London Tate needs additional space to display a collec¬tion that has far outgrown the limited display ar¬eas on Millbank; and the people of Liverpool, presumably, want a gallery that will show work they can enjoy. Director Richard Francis has something of a plate-balancing act to perform.

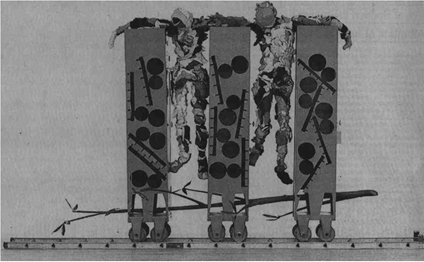

The three exhibitions with which the Tate in Liverpool has chosen to announce itself will be seen, inevitably, as a manifesto, a marking out of the new gallery's territory. They've gone for the Surrealists and Mark Rothko's Seagram Mural Project paintings, in the two downstairs galleries reserved for work from the permanent collec¬tion; upstairs, in the main first floor galleries, there is a large exhibition, "Starlit Waters", made up of Tate acquisitions and loans, devoted to British sculpture since 1968.

There's an element of Safety First here. The Surrealists are a guaranteed popular draw, a bunch of subversives who have been...