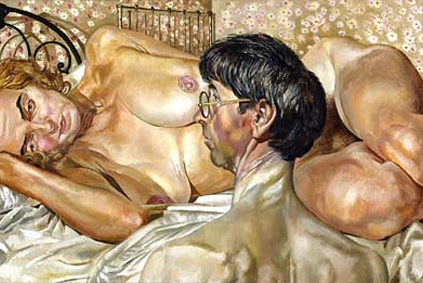

IN 1937 PICASSO painted Guernica, Mondrian started work on Composition with Red Yellow and Blue and Stanley Spencer, a world away from the avant-garde, painted his Beatitudes of Love. Three of the Be-atitudes are in the Barbican's centenary celebration of his work, variations on a favoured Spencer theme: the Matron and the Weed. Spencer's misshapen lovers, kitted out in floral-print dresses and worn tweeds, leer at one another in mutual infatuation. The Beatitudes might easily be mistaken for satire but that is the last thing they were meant to be: Spencer's subject was the transfiguring power of Love.

There is a telling photograph of him on the back cover of Kenneth Pople's new book, Stanley Spencer: A Biography (Collins, pounds 25): a bespectacled gentleman in a stained jacket, he is trundling his easel and paints along a wet country lane in a pram. It is hard to imagine a painter to whom the formal and philosophical doubts that characterised so much of the art of the first half of this century, could have seemed less important. The painter with the pram; the artist who found heaven in Cookham; Stan, Stan, the visionary man - whatever else he was, one thing is for sure. He was no modernist.

Maybe this is why people so often use Spencer to define their sense of the proper forms and subjects of art. Last week, at the private view of the Barbican show, I overheard one elderly visitor insist to his companion that ''Young abstract painters today have no ideas. They have nothing to say. Look at this though pointing at one of Spencer's Marriage at Cana pictures . It's so full, so rich.'' Earlier in the day, I had been interviewing a young abstract painter. He felt genuinely sorry for me when he heard...