In September 1917 the twenty-four-year-old painter Joan Miro wrote to his fellow Catalan and close friend Josef Francesc Rafols about the art of the future. “After the great French Impressionist movement and the liberating Post-Impressionist movements, Cubism, Fauvism and Futurism,” everything served (or so the exuberant Miro believed) “to emancipate the artist’s emotions and give him absolute freedom”. He went on: “I think that tomorrow there will be no more schools ending in ‘ism’ and we will see a canvas painted in a completely different way than a landscape at noon – each thing in life will produce a different sensibility in the free spirit, and we will try to see, through the canvas, nothing more than the vibration of the spirit… May our paintbrush record our vibrations.”

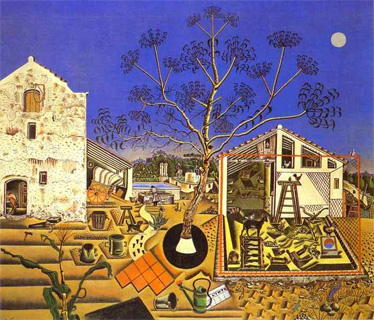

Miro’s attempt to forge or find a new language of painting, one that would live up to the large but as yet unfocussed aspirations expressed in that early letter, is the subject of an exhilarating exhibition currently at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Simply entitled “Joan Miro 1917-34”, the show follows the trajectory of the artist’s early career. Miro was born in 1893, which meant that he was too young to participate in the avant-garde experiments of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but he seems to have been immune to the sense of belatedness that afflicted many other members of his generation. The fact that the artists of the immediate past had broken with so many of the established conventions of painting left Miro with a sense of almost infinite possibility, like a gardener confronted with a bare and newly cleared plot.

The Pompidou exhibition opens with a room full of Miro’s juvenilia. He went to an art school in Barcelona where the teachers were sufficiently up-to-date to encourage the...

Miro at the Centre Pompidou 2004

23-04-2004