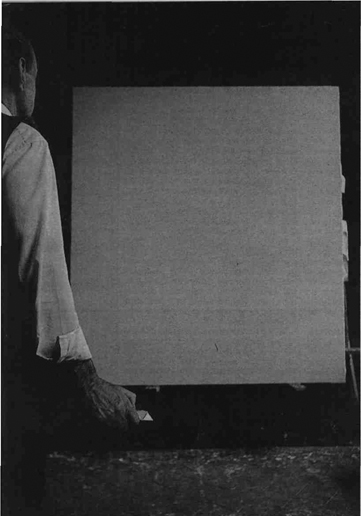

Andrew Graham-Dixon on Lucio Fontana's violent works

ITALIAN cartoonists of the 1940s and 1950s had a field day with Lucio Fontana, the Mila-nese modernist who riddled his canvases with holes or slashed them with a razor blade. They invented fishermen who took to the sea in panic at the artist's approach, terrified that he might punch holes in the keels of their boats; they devised the Lucio Fontana parasol, a jokily ineffectual item which left sunbathers spotted like leopards.

The origins of Fontana's art were, despite the gibes, entirely serious. He was the found-ing father and chief exponent of the Spatialist movement, which published its first Manifesto in 1946. Painting and sculpture were dead, ac-cording to Spatialism (rumours of the Death of Art have been greatly exaggerated, throughout this century). "Man has exhausted pictorial and sculptural forms ... the artistic era of paints and paralysed forms is over... Movement, colour, time and space are the concepts of the new art."

It's hard to say whether Fontana was an ide-alist, prophesying a bright new dawn of mod-ern art, or a cynic whose work stemmed from disillusionment, from a feeling that art, itself, had reached a terminal impasse. Both views receive a measure of support from the White-chapel's retrospective of Fontana's painting and sculpture, the first such show to be staged in this country.

The first Spatialist Manifesto is filled with millenarian statements and naive expressions of hope. It included a request to the world's scientists, asking them "to direct a part of their investigations.., toward the creation of in-struments capable of producing sounds that will permit the development of four-dimen-sional art." Fontana hoped to use the results "to open up space, create a new dimension for art, tie in the cosmos as it endlessly expands beyond the confining picture plane."

The...