Andrew Graham-Dixon reviews new works by Dhruva Mistry and Shirazeh Houshiary

WALTER PATER described Luca Delia Robbia's ceramic reliefs (in The Renaissance) as "those pieces of pale blue and white earthenware, like frag-ments of the milky sky itself, fallen into the cool streets, and breaking into the darkened churches." There is a touch of the Delia Robbias about Dhruva Mistry's new work at Nigel Greenwood: large polychromed roundels, with painted figures, beasts and fragments of architecture, picked out in heavy relief and set on dusty grounds of ethereal pigment.

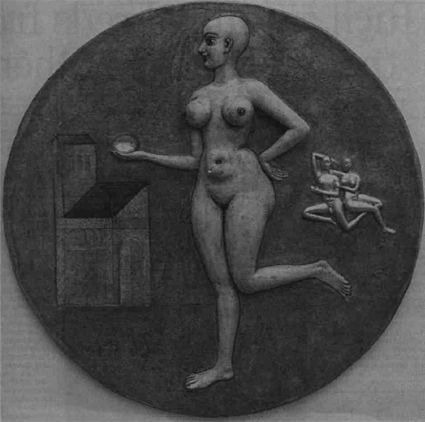

Mistry's pieces have a sacred feel to them, a sense of ritual purpose anach-ronistically at odds with most people's idea of modern sculpture. Strange, bald-headed, pneumatically bosomed god¬desses follow you round the room with the fervent gaze of Moony proselytisers (Mistry purchases the eery enamelled eyes of his figures from a shop in the bazaar in Baroda, the town in India where he took his first art degree). They pose and gesticulate with what looks like veiled symbolic intent, cupping a breast, holding up a golden egg for contempla¬tion — even dreaming, couchant, with a heraldic intensity.

Space and scale, in these shallow plat-ters, are treated with a deliberate disre-gard for naturalism: golden elephants fly around the peripheries of Mistry's circles, dwarfed by his female nudes; a fish attains human stature; diminutive Giottesque churches and temples perch impossibly in the void. There is more here, all this implies, than meets the eye — you detect the muted clash of symbols.

Pater also wrote of della Robbia's art that "no work is less imitable; like Tus-can wine, it loses its savour when moved from its birthplace, from the crumbling walls where it was first placed." Mistry's art, by contrast — a fact emphasised by its newborn arrival in the white-walled vacuum...