The Biplane banks and soars, its pilot presumably about to perform a loop-the-loop or some other feat of aeronautical derring-do. Far below, from his bird's-eye perspective, the Colosseum looks like a broken snail-shell bleached by the sun. Maybe the man at the joystick is Tato himself - like Biggles, he was known by his nickname alone - the artist-aviator who painted this picture in 1931.

Tato's Spiralling in Flight over the Colosseum was always a must for inclusion in the Accademmia Ital-iana's ''Futurism in Flight'', which surveys the work of those Italian artists who aimed to take modernism air-borne. Tato's picture must have seemed, to his colleagues and contemporaries, an emblem for its times. The Colosseum, symbol of the crumbling past, is dwarfed by the biplane, symbol of thrusting, purposeful modernity, screaming through the sky. It's one in the eye, too, for fine art conventions: forget plein-air painting, this is mid-air painting.

This exhibition demonstrates that technophilia, in Italy, died hard. Most British artists who had become infatuated with the Machine Age in the pre- war years were, by 1918, thoroughly disenchanted with a tech-nology whose destructive potential had been so graphically revealed. But in Italy, it would seem, the daring young painters in their flying machines carried on regardless.

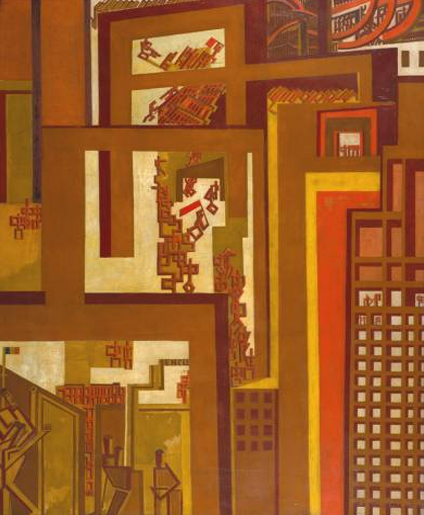

Art became, among other things, a surrogate form of warfare. Painted from the cockpit - although the artist probably had to tidy things up a little in the studio - Tullio Cralli's Dogfight presents you with a fractured view of things. The landscape below tilts crazily as the artist's plane takes what may be assumed to be evasive action, while the wing-mirror discloses the blurred silhouettes of other planes outlined against the cloud cover. This art's spatial complexity, its sense of every-angle-covered, seems to have less to do with the...