IT CAME as no great shock when, on Tuesday evening, John Richardson won the pounds 22,500 Whit-bread Prize for the first volume of his A Life of Picasso. Richardson's acceptance speech, however, may have taken his jubilant publishers by surprise. He chose the moment (with impeccable timing) to suggest that what was first planned as a three-volume work may eventually run to four or even five volumes. Picasso, the most productive and long-lived of twentieth-century artists, was never going to be easy to contain. Such a prolific life demands a prolific chronicler.

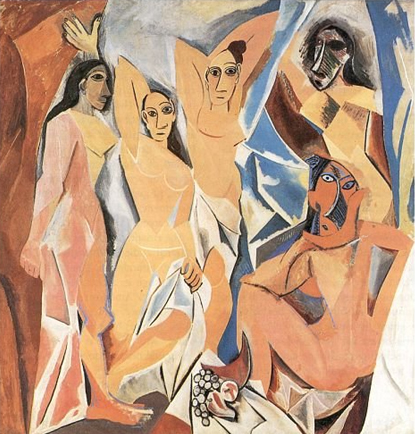

In conversation the morning after the award dinner, Richardson was evidently pleased but just as evi-dently daunted by the scale of the work that still lies in front of him. His first volume ends with the young Picasso about to embark on the most ambitious and significant work of early modernism, and arguably his first major work: the Demoiselles d'Avignon. ''There is so much to do, so much to learn, still,'' says Richardson, almost as if he is talking to himself.

The sheer bulk of Picasso's oeuvre poses unusual problems to the biographer, as does his tangled leg-acy, which is partly the result of the artist's lifelong reluctance to plan for death. (''The worst question you could ask him,'' Richardson says, ''would have been 'Have you made a will?' You just didn't discuss death, full stop.'') Now, as he meditates his second volume, Richardson is still searching for vital evidence concerning Picasso's work of the second decade of the century: a pile of letters and drawings to Picasso from Max Jacob which he found in the artist's studio after his death and which he describes as ''the Rosetta Stone'' for a whole period of Picasso's art. ''Just when I was about to ask Jacqueline, Picasso's widow, to let...