Andrew Graham-Dixon iooks into the camera's obedient mirror at the National Portrait Gallery

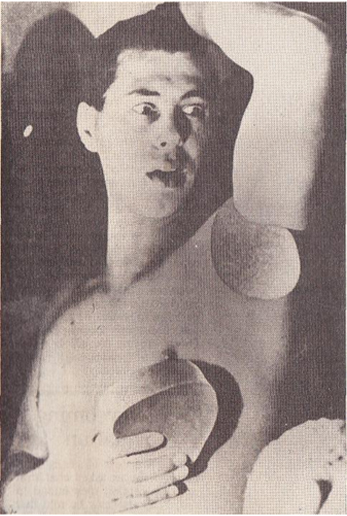

IN 1843 Elizabeth Barrett described the photographic portrait as "the very shadow of the person lying there fixed forever", and declared that "I would rather have such a memorial of one I dearly loved, than the noblest artist's work ever produced". But the idea that photographs, unlike paintings, somehow record the objective truth about people comes under siege in "Staging the Self', an eclectic exhibition of self-portrait photographs from 1840 to the present day. The show memorialises a host of masquerades — a trio of American women in the 1890s don suits and grin imp¬ishly at the camera, looking like transves-tite Charlie Chaplins; Cecil Beaton dresses up like one of Watteau's Arcadian min¬strels and looks wistful, in soft focus; Cindy Sherman, in her "Untitled Film Stills" se¬ries of the Seventies and Eighties, plays with the endless self images cinematic fan¬tasy has bequeathed to the modern wom¬an.

The exhibition presents itself, somewhat portentously, as a history of "the image and idea of the self. Well-meaning educa¬tional placards punctuate the show's progress — a quotation (predictably) from Susan Sontag or Roland Barthes, or some carefully chosen lines by Ezra Pound on looking in a mirror. The images themselves — from Hippolyte Bayard's 1840 Self Por¬trait as a Drowned Man to Robert Mapplethorpe's rouged and lipsticked Autoportrait 1980 — obstinately resist the exhibition's attempt to organise them as a potted visual history of the philosophy of identity. The organisers' lofty cultural am-bitions for the show, epitomised by subtitles like "Beyond the Unitary Self, are sabotaged by the diversity of its contents, and by the unclassifiable idiosyncrasies of the images that line its walls.

Gaspar-Félix Nadar togs himself up as an American Indian in 1863, Looking for all the world like...

Lessons in how to shoot yourself

07-10-1986