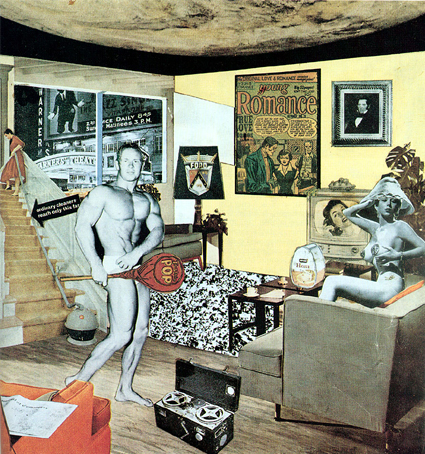

RICHARD HAMILTON is known as the great image-manipulator of post-war British art, and most of his best-known works have taken the form of canny tinkerings with what came to hand: Towards a definitive statement on coming trends in men's wear and accessories, that weird distillation of early Sixties ideas of what it meant to be masculine, culled from underwear ads, sports photographs and shots of JFK; Swingeing London, a news picture of the drugs-busted Mick Jagger and Robert Fraser in the back of a police van, transformed into a grand, summary image of the times.

In advertising terms, you'd call Hamilton a visualiser, but he apparently prefers to see himself in a more Old Masterly light. The Tate Gallery's current Hamilton retrospective has evidently been staged with this in mind. The aim, it is said, is to ''present Hamilton as a painter engaged above all with the longstanding central concerns of art''. Hamilton the traditionalist? This is not entirely convincing.

Not that he never was a traditional painter. Hamilton's paintings of the early 1950s are dry time-and-motion studies, whose subjects - a car, say, seen through the window of a moving train - are pretexts for demonstrations of the truancy of vision. They culminate in a painting of 1954 called Still Life? whose message is, precisely, that life is not still: a group of bottles on a tabletop, rendered in a style which oddly combines analytical clarity with the bleary- eyed vision of a drunk. These are essentially reruns of older forms of modern painting, and they are painted in an openly derivative, Cezannesque style.

What Hamilton seems to have taken away from his early work was the knowledge that painting, per se, was the last thing that interested him. And while the conventional painter's progress leads from derivativeness to...

It's always the thought that counts

30-06-1992