The biographer Mary Trevelyan said that Millais’s portrait of Ruskin “has as much drama behind it as any picture in history”. It is certainly hard to think of a painting created in more turbulent circumstances.

As he set out to to portray Ruskin communing with nature, in the summer of 1853, Millais himself had begun to commune with Ruskin’s young and neglected wife, Effie. While the most celebrated art critic in Victorian England busied himself with the index to The Stones of Venice, Millais and Effie fell in love. Not long afterwards, Effie finally plucked up the courage to challenge the legality of her six-year marriage to Ruskin, on the grounds that it had never been consummated. The marriage was annulled. Millais belatedly finished his portrait of Ruskin. A year later Effie became his wife.

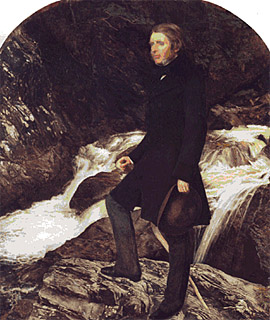

Trevelyan’s absorbing book Millais and the Ruskins (1967) tells the whole story in great detail. But even if the troubled circumstances behind the painting were not known the viewer might still sense that something, here, is not quite right. Ruskin stands before us in a wild natural landscape of the kind that he frequently hymned in his writings. His feet are planted on a boulder of crystalline slate rock, the surface of which sparkles with silvery lichen, while behind him a mountain torrent flows and foams. But “the prophet of nature” seems curiously out of place in this particular corner of the natural world. In his cravat and frock-coat, he is an incongruously urbane figure. He might almost have been cut out from another picture and arbitrarily superimposed here. An alien presence, he seems himself alienated from all the life and beauty that surrounds him, to judge by his glassy stare and his air of incurable introspection.

Millais conceived the picture during what began...

ITP 2: John Ruskin, by Sir John Everett Millais

30-04-2000