Andrew Graham-Dixon reviews the gloomy forests of John Virtue and the dense abstracts of Therese Oulton

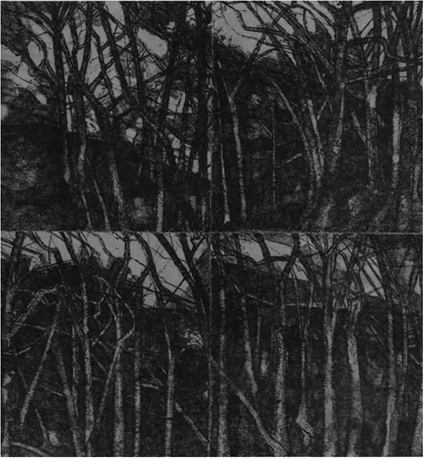

IT IS getting dark. In the twilight, you struggle to get your bearings. Trees block your view at every turn; their splayed limbs seem to gesture, but this wooden semaphore is uncoded, opaque. Houses sometimes loom unexpectedly through the screen of branches, but there is no sign of their inhabitants. You are alone.

Occasionally the prospect widens, affording glimpses of open country. It is unwelcoming terrain, sparsely vegetated moorland crisscrossed by paths that seem to lead nowhere and carved up by walls that serve only to separate one patch of bleakness from another. You return to the arboreal labyrinth and gaze, again, at the dense army of trees that has you surrounded. Some of them look familiar. You realise you have been walking in circles. You are lost.

John Virtue's disorientating land-scapes are real enough. All the works in his current exhibition, at the Lisson Gallery, are based on sketches compiled from on-the-spot observation near his home, in the village of Green Haworth in north-east Lancashire. But in Virtue's art, home ground becomes strangely alien. This is partly down to pictorial innovation. Each of his works is a gridded multiple a chess-board of picture-postcard-sized (or larger) glimpses of his locale, rendered in vigorously woven cross-hatchings of black ink on white grounds.

There is no discernible narrative or topographical logic to Virtue's juxtapo-sitions of image: seven-trees-plus-hill sits next to six-trees-plus-house-plus-different-hill, and so on across and down the picture's surface. At first sight, it all looks a bit perverse: Samuel Palmer meets Andy Warhol. It is perverse. It is also brilliant. This is only Virtue's second exhibition of any note (he is extremely limelight-shy), but it is a revelation. He emerges as a major artist.

Remove...