The year is 1890 and Henri Rousseau, palette in hand, is standing to attention for the occasion of his self-portrait, an arrestingly large picture entitled Myself, Portrait-Landscape. Wearing his painter’s uniform, a dark suit and a black beret of such battered authority that it has a hint of the Napoleonic tricorne about it, he looms large and mannequin-like on a Parisian quayside. Behind him is a cast-iron bridge, beside which is moored a boat festooned with the flags of nations. The painting is, among other things, a monument to the artist’s considerable sense of his own self-importance. The modern city spreads out around him, but he is the biggest thing in it. Bystanders come up no higher than his ankles. Rousseau even manages to dwarf the Eiffel Tower. His face is solemn, set, clenched, a heavily bearded mask of sheer impassivity. A balloon floats through broken clouds in the air above – the painter’s emblem for his own fantasy.

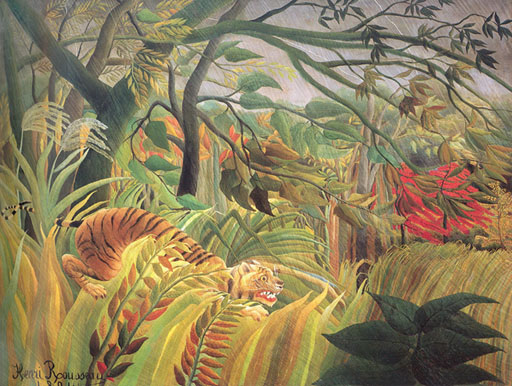

The picture hangs near the start of Tate Modern’s new exhibition, “Henri Rousseau: Jungles in Paris”. It is a graphic illustration of the gulf dividing Rousseau’s view of himself, as a sophisticated modern painter, from the long established popular conception of him as a naïve or primitive artist. “The amusing Monsieur Rousseau will not abandon his attempts at infantile art, which recall toys, the laughable shapes of wooden or gingerbread figures,” wrote a critic for Le Matin back in 1908. Tate Modern’s exhibition is well stocked with just the sort of pictures which that curmudgeon must have had in mind. The jungle paintings are particularly well represented, and aptly so, because they are Rousseau’s finest and most enduringly powerful works – pictures created on the scale of salon history paintings, yet in a style calculated to resemble children’s illustration...

Henri Rousseau: Jungles in Paris at Tate Modern 2005

06-11-2005