The beauty of Richard Avedon's photography is strictly skin deep. Fortunately, says Andrew Graham-Dixon, he has developed an eye for sitters with unusually eloquent skin

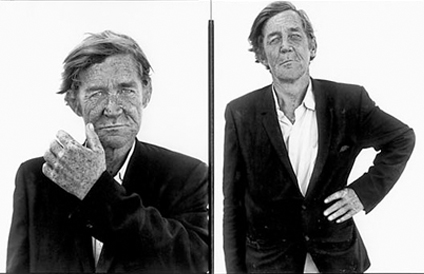

On August 29 1983 Richard Avedon photographed Clarence Lippard. Mr Lippard, who as requested had not shaved or washed his hair or changed his customary appearance in any way for the occasion, stood against the photographer's white backdrop and stared into the lens of the camera. Then he raised his hand, perhaps to brush away a fly or scratch a sudden itch. Mr Avedon asked him to hold it right there, to keep still, please, while he took the picture.

Clarence Lippard, drifter, Interstate 80, Sparks, Nevada is a portrait which also has many of the qualities of a landscape photograph. Seen in void white space, Mr Lippard amounts to foreign territory. His face is a parched wasteland, an expanse of cracked mudflats and fields of scorched stubble. His hair is dry and combustible. His hand is a freckled stone. His alienness is both his weakness and his strength, and he is aware of the fact. He is poor and his clothes are cheap and he does not have a settled place in the world but he is still extraordinary and still his own man. He stares down his photographer with a defiance bordering on contempt. You can get my picture, Mr Avedon, but you can't get me.

The Avedon retrospective which opened last week at the National Portrait Gallery has been called Evi-dence, but Richard Avedon, Drifter might have fitted better. The career that it memorialises comes across as a meander at the end of which a destination is eventually reached and something truly remarkable is done.

"The best portraits," Avedon once said, "are always emperors or postmen. People who are...