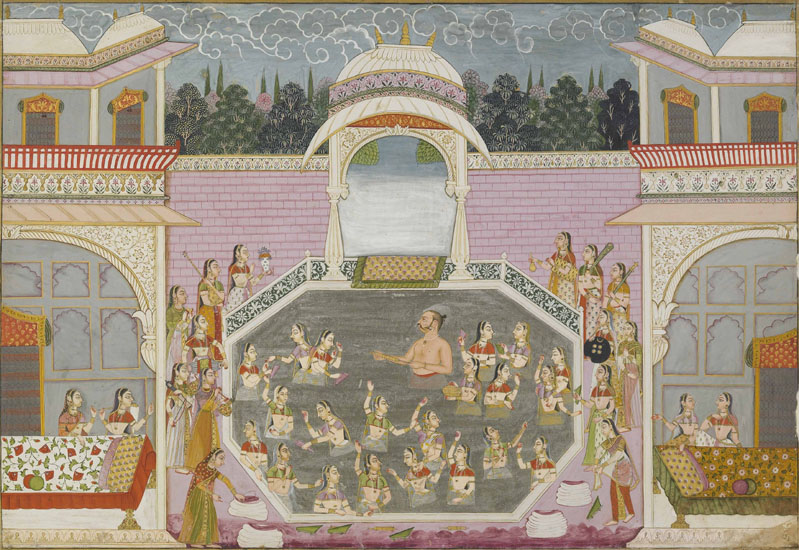

It is full moon during the Hindu month of Phalgun and Maharaja Bakhat Singh is evidently having a whale of a time. Surrounded by the scantily clad ladies of his court, he stands waist-deep in an octagonal pool at the centre of his magnificent palace complex. During the springtime festival of Holi, it is traditional for celebrants to hurl pigment at each other, so the bare-chested Maharajah points a distinctly phallic syringe at his favourite girl, squirting her with a bright jet of coloured water. As a sitar-playing band strikes up, other members of his harem begin a sinuous dance. Nearby, yet more female attendants are smoothing down the flower-embroidered coverlets of two silk-draped beds. It is clearly going to be a long night. Even the clouds in the evening sky, writhing in excited coils, seem caught up in the festive mood.

Maharajah Bakhat Singh Rejoices during Holi was painted by so-called “Artist 3” of Bakhat Singh’s court in about 1750. The picture is one of 54 works in a remarkable new exhibition, “Garden and Cosmos: The Royal Paintings of Jodhpur”, at the British Museum. The assembled pictures, a once-in-a-lifetime loan from the unique holdings of the Mehrangarth Museum Trust, embody a little-known but deeply absorbing school of north-western Indian painting.

Maharajah Bakhat Singh Rejoices during Holi was painted by so-called “Artist 3” of Bakhat Singh’s court in about 1750. The picture is one of 54 works in a remarkable new exhibition, “Garden and Cosmos: The Royal Paintings of Jodhpur”, at the British Museum. The assembled pictures, a once-in-a-lifetime loan from the unique holdings of the Mehrangarth Museum Trust, embody a little-known but deeply absorbing school of north-western Indian painting.

By contrast with the more celebrated productions of Mughal painting, the pictures of Jodhpur tend to be large in format. Their subjects are in many cases familiar – the entertainments of the court, the lives and loves of the gods – but the handling is boldly different. There is a wildness and erotic abandon about many of these works that is alien to much of Mughal art, with its fineness of detail and fastidious sense of sophistication. Celebration of Holi in a Garden Pavilion, painted in the late...