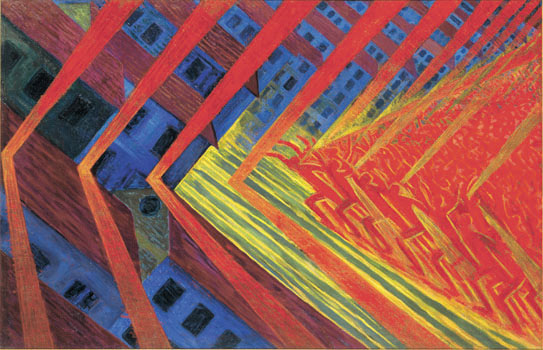

Carlo Carra painted his Portrait of the Poet Marinetti in 1910. The author sits at his desk, eyes blazing, chewing so hard at his cigarette that it has broken off in his mouth. He clutches his pen as if he were about to plunge it, like a dagger, into the sheet of blank paper before him. The air is full of shapes and planes, irregular wedges and diagrams of linear force. Thick red snowflakes fall – a painter’s analogues, perhaps, for the writer’s furious words.

A year or so before Carra painted his picture, Marinetti had composed his Futurist Manifesto, that incendiary bomb of early modernist aesthetics, with its machine-gun rat-tat-tat of demands and desiderata: “We will glorify war – the only true hygiene of the world ... We will destroy museums and libraries ... We will sing the great masses agitated by work ... revolutions in modern capitals ... greedy stations devouring smoking serpents ... and the slippery flight of airplanes.”

“Futurism”, at Tate Modern, celebrates the centenary of Marinetti’s infectiously vibrant tract. Its impact was most keenly felt in his native Milan, where a group of painters calling themselves the Futurists set out to depict the modern city in a manifestly Marinettian manner. Each cultivated his own corners of metropolitan experience. Carlo Carra became a dilettante of the city by night, revelling in the spectral effects created by streetlamps and neon and the headlights of onrushing trams. His Nocturne in Piazza Beccaria, of 1910, pictures the city as an enchanted blur, a parallel universe where a hundred suns blaze, turning people buildings into atomised and ghostly shadows. In Leaving the Theatre, painted in the same year, women leaving La Scala in their evening finery are incendiarised by glaring streetlamps. They look less like people...